Storbritanniens ambassadør (high commissioner) i Kenya har måttet undskylde et uhørt hårdt angreb på regeringsinspireret korruption i det østafrikanske land, som han anslår har kostet kenyanerne mindst 188 mio. dollars (1,15 milliarder kr.) siden præsident Mwai Kibaki tog over i januar 2003 – efter at han netop havde vundet parlamentsvalget på løfter om at udrydde den altomsiggribende korruption, rapporterer BBC Online Torsdag.

Men high commissioner Edward Clay holdt fast i, at emnet var relevant at rejse. Han fik valget mellem at konkretisere sine beskyldninger eller udsende en officiel undskyldning senest kl. 12 lokal tid torsdag. Han valgte det sidste efter et 30 minutter langt møde med udenrigsminister Mwakwere, der udtrykte skuffelse over ambassadørens bemærkninger og vrede over, at han ikke havde fulgt de diplomatiske kanaler, men sagt dem offentligt i en tale til britiske forretningsfolk i Nairobi.

I talen anklagede Clay unavngivne embedsmænd og politikere for at opføre sig som “grovædere” og “brække sig på donorernes sko”. Og han fik opbakning fra lederen af Kenya-afdelingen af anti-korruptionsvagthunden, Transparency International, Gladwell Otieno:

– Vi oplever i disse måneder en klar tilbagekomst af den store korruption (store bestikkelsesbeløb i modsætning til klatskillingen til politimanden) på højt niveau i samfundet. Pengene er gået til nyskabte ministerier, til flunkende nye biler og kontorer. Folk har ret til at undre sig over, hvad der egentlig foregår, sagde han ifølge BBC.

Kibakis regering svarede med at opregne en liste over tiltag, der er taget siden den nye Regnbuekoalition kom til magten for halvandet år siden:

– Den har reformeret retssystemet – over halvdelen af alle dommere er fyret efter afsløringer af omfattende korruption

– Den har taget strenge disciplinære forholdsregler mod korrupte politibetjente og deres foresatte

– Den har taget omgående skridt til at korrekse forholdene efter at der blev opdaget store uregelmæssigheder ved indgåelsen af en offentlig kontrakt (et af de mest fede korruptions-ben)

– Den har oprettet en særlig enhed for etik og god regeringsførelse direkte under præsidentens kontor.

Ambassadør Clay sagde blandt andet

– at listen over regeringsmedlemmer og fremtrædende embedsfolk, som ikke var korrupte, kunne stå på et postkort, jå måske på bagsiden af et frimærke

– at der var gjort flere forsøg på at vingeskyde de nye organer, som var oprettet for at bekæmpe korruptionen

– at en kontrakt til en værdi af over 125 mio. dollars var givet til et selskab, som “ikke engang kunne gøre en have i stand, og som aldrig har leveret andet end tegninger på bagsiden af en konvolut og ellers kun varm luft”.

Læs hele Edward Clays tale her, gengivet på originalsproget

Text of a speech made by UK High Commissioner to Kenya, Edward Clay, to a group of UK businessmen, as passed to the BBC by the High Commission:

Corruption: my major theme, inevitably, given the prominence the subject currently enjoys.

Why does it matter? After all, against a World Bank figure of 1 trillion US dollar spent on bribes each year, Kenya perhaps accounts for only 800 million dollar or so, annually, since the 2002 election.

It is pretty staggering to think bribes were worth about 3 per cent of world GDP at the time of the study I have just mentioned. But it is outrageous to think that corruption accounts here and now in Kenya for about 8 per cent of Kenyas GDP.

The science is not exact, but I think the message is clear: Kenya, which scores low on almost every indicator that matters these days, has a burden of corruption that is large compared to its peoples diminishing wealth. It is using up its own quota of 3 per cent, plus also the unused quotas of Finland or perhaps all of Scandinavia.

“Patriotism”

What business is it of ours? It was only a matter of time before somebody piped up with the old saw “keep yourself out of our domestic business”.

There was such a columnist in Sundays “Nation” who wrote “Any patriotic Kenyan should get offended when a group of foreigners criticise the same institutions we criticise”.

So it seems that a truly patriotic citizen is one who has to defend those who abuse his ideas of right and wrong, whom he may have voted for or accepted his/her authority as legitimate, simply because they share a citizenship in common.

Behind such patriotism, an army of scoundrels could find refuge. The institution we are criticising, in case the writer has not noticed, is corruption.

Well, corruption is not just the business of Kenyans. This country extended to outsiders the promises it made to its own people in respect of governance. Tackling corruption was one of the pillars of the understandings they reached with development partners which saw Kenya go back “on track”.

We are one of the partners to those understandings. When they are broken we feel let down. And we are invited to channel funds into a government which cannot be relied upon to spend money properly, on the basis of proper authorisations, for the purposes for which it was voted. So I feel disappointed; but I also feel outraged on behalf of a country I feel an affinity for. Why?

Kenya is not a rich country in terms of large oil deposits, diamonds or some other buffer which might featherbed a thorough-going culture of corruption. What it chiefly has is its people – their intelligence, work ethic, education, entrepreneurial and other skills. That is what we mean when we talk of Kenyas potential ability to regain its diminishing economic and other leadership in the region.

But those assets will be lost if they are not managed, rewarded well and properly led. One day we may wake up at the end of this gigantic looting spree to find Kenyas potential is all behind us and it is a land of lost opportunity.

Corruption and poverty

It is not the most corrupt country in the world: Transparency International in 2003 reckoned there were ten worse countries including Angola, Myanmar (Burma), Haiti, Nigeria and Bangladesh.

It is, however, behind Uganda, well behind Tanzania, and even behind Libya, Congo, Zimbabwe, Sudan and other countries we would much less like to live in.

A World Bank report in 1997 showed a clear negative correlation between the level of corruption, as perceived by business people, and both investment and economic growth. Where corruption was highest and the predictability of payments and outcomes lowest, investment averaged 12,3 per cent of GDP; where corruption was low and predictability high, the ratio was 28,5 per cent.

The same research shows that countries which reduce corruption and improve their rule of law can increase their national income by four times over a long run and reduce child mortality by as much as 75 per cent.

The other negative impacts of corruption include

aggravating income inequality and poverty;

lowering investment and retarding growth;

reducing the volume and effectiveness of development assistance;

discouraging domestic saving;

bent procurement processes leading to low quality infrastructure;

increasing and unpredictable transaction costs;

and, of course, the deviations involved in selecting national priorities not on the basis of the Economic Recovery Strategy but on the basis of what pays well in hidden kickbacks which can be concealed somehow in the national budget.

All of these features are present in Kenyas case, as I think you could testify.

Progress

Perhaps the most insidious thing is that, spreading from the top and the inside of government outwards, a culture of corruption has spread itself throughout the country.

There must be few and fortunate Kenyans who do not believe that exploiting a relationship, or proffering “kitu kidogo” or having some illegitimate inside track is absolutely essential to getting some ordinary public service, on top of paying whatever the fee is and meeting whatever the legal requirements are.

Last year, we all applauded the legal framework established to try to squeeze corruption and the culture of corruption out of government. We approved of the creation of the Office of Governance and Ethics and the appointment of its Permanent Secretary, responsible to and enjoying the full authority of the President.

Now, there has been progress, undoubtedly. The institutions enjoy some credibility: we ourselves have reported cases occurring within the High Commission which appear to involve attempted fraud and soliciting for bribes. At a low level, there has been some impact: Transparency International noted this year that the public reported fewer cases of petty bribery; but an increase in the size of each bribe solicited.

Right now it is grand corruption which fills the headlines. As Goldenberg draws towards the end of its hearings, the list of the previously great and good mentioned one way or another is impressive. Yet now it is the corruption of the present government which needs more urgently to be addressed.

“Gluttons”

We never expected corruption to be vanquished overnight. We all implicitly recognised that some would be carried over to the new era. We hoped it would not be rammed in our faces. But it has: evidently the practitioners now in government have the arrogance, greed and perhaps a desperate sense of panic to lead them to eat like gluttons (grovædere, red.).

They may expect we shall not see, or notice, or will forgive them a bit of gluttony because they profess to like OXFAM lunches. But they can hardly expect us not to care when their gluttony (grovæderi, frådseri) causes them to vomit all over our shoes; do they really expect us to ignore the lurid and mostly accurate details conveyed in the commendably free media and pursued by a properly-curious parliament?

The worst feature of the last year has been the repeated attempts to undermine the effectiveness of the Office of Governance and Ethics. This was established under a figure of high standing, to crack grand corruption. It was to enjoy the full backing of the Presidents authority, and its boss was to have direct access to the President.

Efforts to kneecap (vingeskyde, red.) this body culminated in the announcement, apparently in error, on 30 June that it was to be removed from the Office of the President and placed under the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs. The “decision”, whoever made it, seems to have been reversed within 48 hours of being made.

Two consecutive decisions within a period of days, one in contradiction of the other, suggested a lack of consistency on a most important matter, or a lack of proper sense of direction, or perhaps an effort at sabotage.

Hot air

But the circumstances prompted the EU and a group of other donors to make public statements of protest. This second group, including the US, Canada and us, followed up a joint call they had made on the President on 3 June with a joint letter, accurately précised in the press. We shall be doing more. I have spoken twice to the Head of the Civil Service in the last 3 weeks, once alone and once with some other donors.

I am still trying to get rid of a sense of guilt: he made me feel I was foolish and misled. He is perhaps trying to whistle up his courage, aware that we know a lot, but perhaps uneasily aware that he does not know just how much we know; equally, he will be aware that we know how much he knows and wonder why more energetic action is not being taken on the strength of what he already knows or suspects.

The facts are – although we cannot be precise about the numbers, they are likely to be an underestimate than otherwise – that the new corruption entered into by this government may be worth around Shs 15 billion (188 million US dollar) a bit less than the World Banks funding of the Mombasa-Malaba road; a bit more than what Health Minister Charity Ngilu expects to get from the Global Fund for tackling malaria); the continuation of old corruption inherited from the last government might be Shs 80 billion.

So we are clear what the magnitude of those figures represents, let us look at the first of the two notorious contracts with… a shadowy company with links to an address in Liverpool, with links to Kenyans, not registered in either Britain or Switzerland, incapable of commissioning a garden shed and discovered never to have delivered anything more than drawings more or less on the back of an envelope, and hot air:

Just the first contract with them is about equivalent to what the European Commission might consider giving to Kenya over three years by way of budgetary support – Euros 125 million.

The value of the Shs 15 billion corrupt deals originated and negotiated under the present government would also buy 1.000 Mercedes S350s: keep your eyes open for them and their drivers (or more interesting, passengers).

Fund the construction of 15.000 odd new classrooms (just under half the number the Ministry of Education says it needs): but I doubt it is worth the trouble your trying to spot them.

Donor fatigue

You need to love this country very much to work to make your business so successful that you can contemplate so much of its earnings being looted by the servants of the state and their friends, and possibly even some of your own friends.

But there is worse to come. Shs 80 billion is the estimated value of old crooked business corruptly carried forward in the 18 months since NARC (the new government, red.) took office.

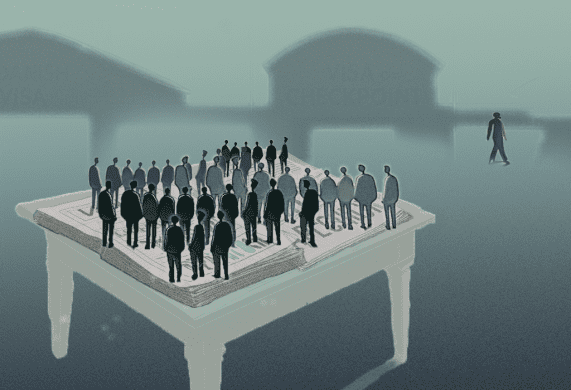

(Finansminister, red) Mr Mwiraria allocated in his budget for next year a shade more than that (Shs 86 billion) for development; he banked on over half of that coming from donors. I doubt it will: the longer the government fumbles its response to corruption and tries to protect the high officers involved, the less likely the Ministers gamble on the donors generosity is likely to pay off.

Or you might say that if Kenyas governance was less corrupt he could afford to pay his own development budget, and not come to donors cap in hand and with fingers crossed. Kenya remains, after all, a country relatively less dependent on donors than its neighbours.

To put it more constructively, he could have a much larger development budget: Kenyas own contribution and one of matching size from development partners glad to help defeat poverty in support of a government in whose policies and practices they had confidence.

These are all big sums. The comparisons of the opportunity costs they represent are staggering.

Some allegedly sober people have reproached the media for being “sensational” in building up these scandals. Such calls for media responsibility are usually a way of covering up threats. The fact is there would have been no disclosure had it not been for the press. It is the truths they have laid bare that are sensational and they need no dressing up.

If the investigations went on and appropriate action followed, we might say that corruption was deplorable, we were sorry it was still going on, but we accepted Kenya was still fighting and winning the battle and that government was genuine in its efforts.

Evidence that would be persuasive would be prosecutions; and the standing aside of those names recently mentioned in connection with the current investigations until those inquiries have been completed.

However, the signs are otherwise. The old dragon has turned on its tormentors just as used to happen in the previous regime (under President Moi):

veiled threats at the media, who should behave “responsibly”;

real red-blooded threats to fix, nobble or even damage those who want to investigate the corrupters;

statements whitewashing in a pedantic, lawyerly way those who were not involved in one deal when investigations- not under the control of the Head of the Civil Service – were still under way to find out who else was involved in some way, which is much more fascinating.

And at the same time, the corrupt are still cutting deals like there was no tomorrow.

“Kings breakfast”

Perhaps your new newsletter should run a competition inviting readers to name those they are confident are not involved: the answers could surely go on a postcard or possibly a postage stamp.

Kilde: BBC og det britiske udenrigsministerium