Another School Barrier for African Girls: No Toilet

Researchers throughout Sub-Saharan Africa have documented that lack of sanitary pads, a clean, girls-only latrine and water for washing hands drives a significant number of girls from school, reports the World Bank press review Friday.

The UN Childrens Fund (UNICEF), for example, estimates that one in 10 school-age African girls either skips school during menstruation or drops out entirely because of lack of sanitation. The average schoolgirls struggle for privacy is emblematic of the uphill battle for public education in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among girls.

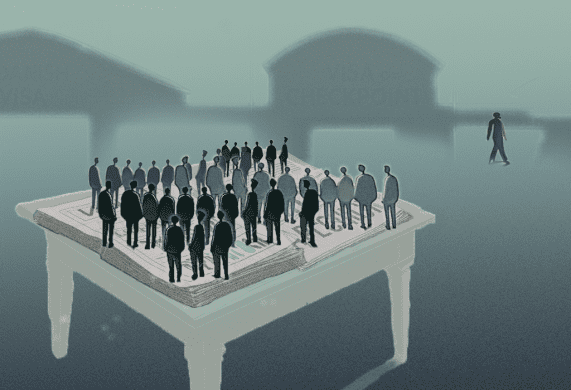

With slightly more than 6 in 10 eligible children enrolled in primary school, the region’s enrollment rates are the lowest in the world. Beyond that, enrollment among primary school-aged girls is 8 percent lower than among boys, according to UNICEF.

And of those girls who enroll, 9 percent more drop out before the end of sixth grade than boys. African girls in poor, rural areas like Balizenda, Ethiopia are even more likely to lose out. The World Bank estimated in 1999 that only one in four of them were enrolled in primary school.

The issue, advocates for children say, is not merely fairness. The World Bank contends that if women in Sub-Saharan Africa had equal access to education, land, credit and other assets like fertilizer, the regions gross national product could increase by almost one additional percentage point annually.

Mark Blackden, one of the Banks lead analysts, said Africas progress was inextricably linked to the fate of girls. – There is a connection between growth in Africa and gender equality. It is of great importance but still ignored by so many, he noted.

The pressure on girls to drop out peaks with the advent of puberty and the problems that accompany maturity, like sexual harassment by male teachers, ever growing responsibilities at home and parental pressure to marry.

Female teachers who could act as role models are also in short supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: they make up a quarter or less of the primary school teachers in 12 nations, according to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Florence Kanyike, the Uganda coordinator for the Forum of Women Educationalists, a Nairobi-based organization that lobbies for education for girls, said the harsh inconvenience of menstruation in schools without sanitation was just one more reason for girls to stay home.

Increasingly, international organizations, African education ministries and the continents fledgling womens rights movements are rallying behind the notion of a “girl friendly” school, one that is more secure and closer to home, with a healthy share of female teachers and a clean toilet with a door and water for washing hands.

In Guinea, enrollment rates for girls from 1997 to 2002 jumped 17 percent after improvements in school sanitation, according to a recent UNICEF report. The dropout rate among girls fell by an even bigger percentage.

Schools in northeastern Nigeria showed substantial gains after UNICEF and donors built thousands of latrines, trained thousands of teachers and established school health clubs, the agency contends.

Ethiopia has also made strides. More than 6 in 10 girls of primary-school age are enrolled in school this year, compared with fewer than 4 in 10 girls in 1999. Still, boys are far ahead, with nearly 8 in 10 of them enrolled in primary school.

UNICEF is building latrines and bringing clean water to 300 Ethiopian schools. But more than half of the nations 13.181 primary schools lack water, more than half lack latrines and some lack both. Moreover, those with latrines may have just one for 300 students, Therese Dooley, UNICEF’s sanitation project officer, said.

In theory, at least, outfitting Ethiopias schools with basic facilities can be cheap and simple, she said. Toilets need be little more than pits and concrete slabs with walls and a door; rain can be trapped on a school’s roof and strained through sand.

Still, she said, toilets for boys and girls must be clearly separate and students who may have never seen a latrine must be taught the importance of using one. And the toilets must be kept clean, a task that frequently falls to the very schoolgirls who were supposed to benefit most.

Kilde: www.worldbank.org