Mens verdens øjne fokuserer på præsidentopgøret i Elfenbenskysten, lider befolkningen på grund af stigende fødevarepriser. Priserne på basisvarer som olie, ris og mel er i nogle tilfælde dobbelt så høje som inden krisen.

For now the crunch is hitting mostly poor families, Ivoirians in the commercial capital Abidjan told IRIN. This is a growing population group. “Poverty has increased on a steady trend in the past 20 years as a result of the successive socio-political and military crises,” IMF said in a May 2009 country report.

“We’re at the end of our tether,” Françoise Mahan, a midwife in Abidjan’s Abobo District, told IRIN, one month after the presidential run-off election which ended in unprecedented deadlock with two political camps claiming power. Already after the October first round, tensions led to some prices creeping up.

“I can no longer get what I need at the market with 2,000 CFA francs [$4] for my family of three. Now I need about 50 percent more – but at the moment we just can’t afford that.”

Food prices are soaring in Abidjan and other main cities. In the northern city of Odienné and in Gagnoa in central Côte d’Ivoire, before the election crisis a kilogram of sugar cost the equivalent of about $1.25. It now costs $2.40; and the same goes for a litre of cooking oil.

Vi har ikke råd til at strejke

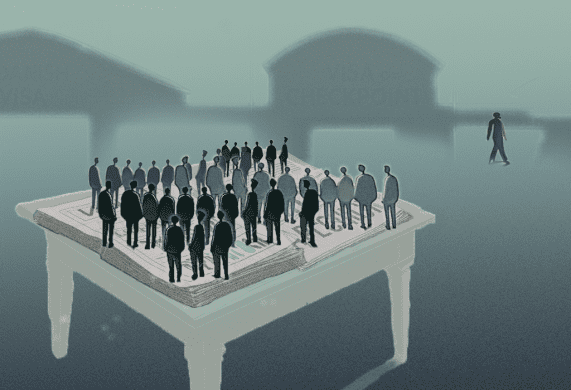

As the government of the internationally recognized president, Alassane Ouattara, called for a nationwide strike to begin on 27 December – to try to force incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo to step down – many Ivoirians are simply trying to make ends meet.

“We heard about the strike call,” said a youth in the central town of Gagnoa. “But it’s the holiday season and some people wanted to come out and try to make at least a bit of money.”

For now petrol prices, which fluctuate periodically, have not yet risen significantly during the crisis; but chauffeurs told IRIN given the instability fewer drivers are venturing out and transport prices – for both passengers and goods – are up.

“Some of our colleagues have not come out because of the strike,” Abidjan taxi driver Drissa Fofana told IRIN. “But we’ve got to feed our families. The situation is tense so we take the risk; we’ve doubled our tariffs, even if petrol prices have remained the same.”

Karim Koné, petrol station attendant in Abidjan’s Adjamé District, said he eats less per day to make whatever food the family has go further. “I’ve started depriving myself of food during the day. I prefer to leave whatever I’d eat in the middle of the day for the family’s evening meal.

A 5 December joint statement by the African Development Bank and World Bank expressed concern about the political situation’s impact on the average Ivoirian. Having re-engaged in Côte d’Ivoire in 2008 after suspending relations in 2004, the World Bank has closed its office in the country and stopped disbursing funds since the election crisis.

“The sustained crisis in Cote d’Ivoire will drive many more Ivoirians further into poverty and hurt stability and economic prosperity in the West African sub-region,” the statement said.