Omkring 50 procent af Burundis befolkning er underernæret, og godt 60 procent kan ikke være sikre på, at de får mad på bordet hver dag. Det kan skabe sociale spændinger, advarer hjælpearbejdere.

BUJUMBURA, 23 February 2011 (IRIN): High food prices, increasing malnutrition and the impact of La Niña are Burundi’s major humanitarian concerns as the country moves from post-conflict to a development phase, say aid workers.

“We need to absolutely address the basic needs of the population before we go beyond that,” Jean–Charles Dei, the acting humanitarian coordinator for Burundi, told IRIN. “As [members of] the international community, we are monitoring the situation, trying to extinguish fires … [such as] pockets of cholera, measles, diarrhoea or malnutrition.”

After years of civil war in the 1990s, Burundi has embarked on economic recovery but aid workers say much more needs to be done to ensure basic needs are addressed. The war deprived the population of their rights to basic services such as health, education and sanitation.

The infrastructure was extensively damaged and the little that remained intact has not been maintained, with drastic consequences for the provision of health services as preventable or previously eradicated diseases are making a comeback.

“We had cases of polio some months back; there are cases of measles and cholera, which has reached epidemic proportions, mainly because of poor access to water and sanitation,” Dei said. “In parts of the country, most notably in the highlands, there is an ongoing epidemic of malaria.”

The chronic malnutrition rate in Burundi is above 50 percent and more than 60 percent of the population is considered to be food-insecure.

In August 2000, a peace accord was signed in Burundi, bringing to an end more than a decade of ethnic conflict. Local and presidential elections were held last year but the post-election period has been marked by a deepening sense of insecurity and fear.

The most affected regions are Bugesera – covering the northern provinces of Kirundo and part of Muyinga provinces – as well as the Moso region, including the eastern provinces of Ruyigi, Rutana, Cankuzo and parts of southern Makamba province.

The harvest for the 2011 agricultural season, known as season A – from September to February – will not ameliorate this situation because of the La Niña phenomenon, which has hit most of the food-insecure regions.

The latest bulletin by the country’s food security early warning system indicates that the La Niña-induced rain deficit in some highland regions and floods that have damaged crops in these areas have compromised the chances of a good harvest for season A.

On 12 February, two people died and 10 were injured at Mena in Bujumbura Rural’s Kabezi commune when their houses collapsed following heavy rains. Kabezi administrator Léonce Ndinzirindi said 100 houses and several hectares of cassava, beans and bananas were destroyed.

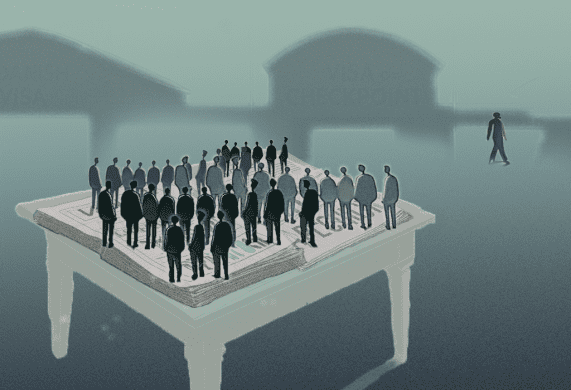

Access to food, therefore, remains a crucial challenge and an area of concern for the humanitarian community as it could compromise Burundi’s chances for stability.

“If we do not pay special attention to feeding people, what may happen is that those people, because of poverty, can develop negative coping mechanisms with the risk of being easily enrolled in armed groups or bandits,” Dei said. “This is a situation we can avoid; this is the main worry we have in this country today.”

Dei said a national investment plan for agriculture exists, which would allow the country to access funds from global agriculture and food security programmes managed by the World Bank.

Dei said the UN Word Food Programme (WFP) was monitoring the most vulnerable among the population and had developed a mapping system to identify when the situation became critical.

He said WFP was also looking at “a new cash and voucher system that will help vulnerable groups purchase needed staples during this period of high prices”.

“The international community should pay attention to what is happening in Burundi because poverty and the huge effects of the social political crisis on the population could create social tension,” Dei said.