Fredsofre i Duékoué-distriktet ses som optakt til bilæggelse af etniske stridigheder, men mange internt fordrevne er bange for vende hjem.

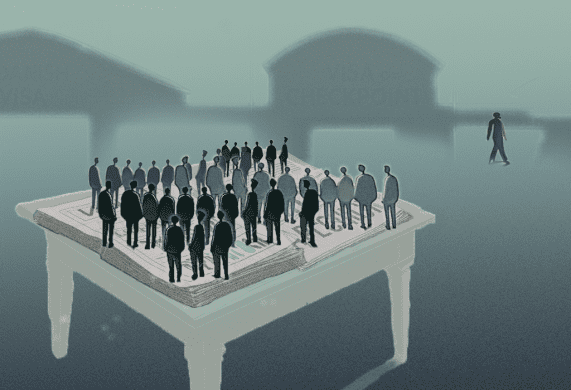

DUEKOUE, 26 April 2011 (IRIN) – For the first time since post-election violence hit the cocoa-rich district of Duékoué in western Côte d’Ivoire, Kouadio, a farmer of the Baoulé ethnic group, entered the grounds of the Catholic mission on 22 April, where some 27,000 people, mostly Guéré, have sought refuge.

Kouadio has grown cocoa on a Guéré-owned plantation near the village of Toa-Zéo, 5km from central Duékoué, since 1997. “I was afraid to come inside, but today when one of the family members came to meet me at the gate I decided to come in,” he said.

Guéré landowners say they have been attacked in recent months by people of the Baoulé, the Mossi (from Burkina Faso) and other ethnic groups who have farmed in the region for decades. Land disputes – occasionally violent, with offences on both sides – are not new in western Côte d’Ivoire.

Landowners and growers say the post-election crisis, in which Alassane Ouattara and Laurent Gbagbo both claimed the presidency, raised tensions to a new level, triggering violence in which countless homes were destroyed, tens of thousands of people of various ethnic groups were displaced and an unknown number killed.

Gbagbo has broad support among the Guéré; Burkinabé and Baoulé (ethnicity of former president Henri Konan Bédié, who backed Ouattara in a run-off) – whomever they might have voted for – are seen as pro-Ouattara. Guéré say Ouattara’s victory has been an opening for attacks on them in “a settling of scores”.

In the 1960s and ‘70s migrant farmers from neighbouring countries and other parts of Côte d’Ivoire came to work on the west’s rich coffee and cocoa plantations owned by native Guéré families.

In the landowner-farmer relationship, growers traditionally make symbolic offerings to owners – part of the harvest or gifts on special occasions like wakes, according to a study by the Norwegian Refugee Council and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. In what landowners and farmers said could be a sign that the communities might once again co-exist in peace, some Baoulé and Burkinabé growers have come to the Catholic mission to greet landowners, express regret about their displacement and offer them food and money.Kouadio said it pained him to know his landowners were living in difficult conditions. “That’s why I came to see them. I plan to come again tomorrow with some food for them. It’s because of the conflict that these landowner families are displaced.”

Baoulé and Burkinabé who farm cocoa near Toa-Zéo – one of several villages from which families have fled – told IRIN they wanted landowners to return to the village. “My prayer is that they will all return, and that everyone can live together as before,” Kouadio said.

Doubts

Omar (nor his real name), a Burkinabé who also grows cocoa in Toa-Zéo, has made several visits to the mission to talk with owners about returning. On 21 April he took two Guéré youth to the village to spend the night and report back to other families.

“Each village has its own unique situation,” Omar said. “I can only speak of our village of Toa-Zéo. There, the war is over – nothing will happen to our landowners if they return. We don’t care about politics… Never again do we want to see this kind of violence.” He added that it would be important initially for aid groups to help families reinstall in the village.

Apparently not everyone is interested in reconciliation. Recent gun and machete attacks in villages near Guiglo, a town 30km southwest of Duékoué, have many displaced people afraid to return home. A 30-year-old woman in Guiglo showed IRIN deep machete wounds in her head and neck, and said her seven-year-old child was killed in the mid-April attack.

At the Duékoué Catholic mission, landowner Téhé Fié Ernest, who fled his village in December 2010, told IRIN: “Initially when some of the growers on our land wanted to come and meet with us, other farmers rejected the idea, saying reconciliation was out of the question… Naturally, that’s worrying for us.”

Cocoa grower Kouadio told IRIN he and others were eager to have Guéré families return to Toa-Zéo, but “I can’t know what all farmers think about all this… the majority at Toa-Zéo say the fighting is over and the owners should come back.”

Trust in new authorities

Guéré at the Catholic mission said given the recent fighting, and that Ouattara was now in power, they must have assurances that local authorities would support them. Residents of Carréfour, a predominantly Guéré neighbourhood, said an attack on 29 March was carried out by groups allied to pro-Ouattara soldiers, and they could not yet trust the new government’s security forces.

Several Guéré expressed worry about traditional hunters called “dozo” – from the north, a Ouattara support base – saying the dozo roamed the bush and attacked people trying to return to their villages.

“The new president must tell them to leave us be, to put down their arms, to let us return to our villages so we can resume our lives and our children can go to school,” Richard, a Guéré landowner, told IRIN.

Landowner Téhé said harassment of Guéré since pro-Ouattara forces seized the area in late March has lessened slightly in recent weeks. “We are able to move about more freely in central Duékoué than a few weeks ago, and that indicates the authorities are working to bring order,” he said.

“Now they must broaden these efforts [to include] our villages and plantations… The new president must show that he has come for all of Côte d’Ivoire’s [more than 60] ethnic groups. He must address the problems in the west immediately, and enforce the law equitably.”

Displaced communities at the mission have been holding regular meetings, including with local authorities, to discuss measures to facilitate and secure families’ return to their villages.