Kathmandu-dalen i klodens højeste bjergkæde er det sted i verden, hvor chancen er størst for at blive ramt af et voldsomt og ødelæggende jordskælv – FN-nyhedstjenesten IRIN opstiller et scenarie over mareridtet og dets konsekvenser, time for time.

KATHMANDU, 26 April 2013 (IRIN): It is the nightmare scenario aid workers and government officials have long feared: a massive earthquake striking Nepal’s densely populated Kathmandu Valley, with tens of thousands feared dead.

In terms of per capita casualty risk (antal kvæstede i forhold til indbyggere), the valley – as the area is known locally – is the most dangerous place in the world.

The capital city and its surrounding suburbs of some 2,5 million people sit in one of the most seismically active areas of the world.

And declining or non-existent construction (bygnings) standards, haphazard (uovervejet) urban development and a population growing 4 percent annually have compounded (øget) the risk.

While disaster preparedness awareness has increased, protracted (langvarig) political instability has weakened risk reduction potential.

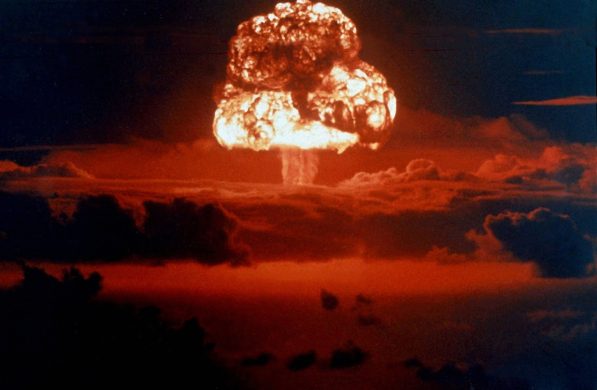

The last major earthquake (1934) flattened Kathmandu, killing thousands and destroying 20 percent of the city’s buildings.

Hour by hour

IRIN sat down with leading international and Nepalese experts at both the National Society for Earthquake Technology and the Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium to determine how such an earthquake might play out today.

10.05am early May

– An intensity IX (Mercalli scale measure) earthquake hits Kathmandu Valley when school is in session (åbne) and people are at work.

10.09

– Immediate aftershocks stop. Some 60 percent of buildings have been damaged or completely collapsed. Few schools remain standing. Schoolchildren in Kathmandu are 400 times more likely to be killed by an earthquake than those in Kobe, Japan.

The US Geological Survey first reports the earthquake, information some newswires pick up, but few details emerge. Mobile phone towers are damaged severely, internet communication is down and electricity coverage is out.

10.45

– Significant aftershock lasts 90 seconds. Now 80 percent of buildings are damaged or destroyed. Only a handful of healthcare facilities remain standing.

Residents work feverishly to dig out loved ones using nothing more than their bare hands. The first 72 hours are seen as critical.

A 2001 seismic risk assessment of one of the capital’s (and country’s) main hospitals identified weaknesses, which were only partially addressed as hospitals failed to get the funding they needed.

In the quake’s epicentre, only doctors and health workers, who were on duty when the quake hit, are able to work; others are either injured or blocked from reaching health facilities due to rubble. Many have died.

12.00 noon

– Domestic trained “light” search and rescue teams (able to search the surface of a collapsed structure but not venture inside) begin their work. However, capacity is limited and many teams have not been properly trained.

Although deployed, international urban search and rescue teams are still unable to reach Kathmandu.

Access to facilities and vehicles is thwarted (forhindret) by rubble (ruiner), and communications are spotty as only radio and satellite phones function. Foreign embassies use their radio systems to check for survivors.

The government’s National Emergency Operations Centre provides the first official – and skeletal – report on the earthquake.

Læs videre på

http://www.irinnews.org/Report/97925/Imagining-a-major-quake-in-Kathmandu

Begynd fra: “3pm (kl. 15) – Embassies attempt to direct their citizens to meeting points, but databases are not…”