Tusinder af fordrevne er tilbageholdende med at vende hjem af frygt for social udstødelse eller direkte forfølgelse i det enorme ørkenagtige land i Vestafrika, som er forsvundet fra avisernes forsider efter islamisternes fordrivelse nordpå af et fransk-ledet ekspeditionskorps.

GAO, 23 October 2013 (IRIN): Mali’s recent conflict has degraded (slidt på) social relations, leading to fears of reprisals among some of the displaced and posing major hurdles to reconciliation (forsoning), observers say.

Mali plunged into chaos with the March 2012 ouster of President Amadou Toumani Touré, which eased the capture of the country’s north by Tuareg separatist rebels, who were later dislodged (hældt ud) by heavily armed Islamist militants.

Across Mali, many blamed the Tuareg and Arabs for helping the Islamist take-over of the much of the north.

When French forces intervened in January to expel the militants, many Tuareg and Arabs were targeted by civilians, and a climate of suspicion engulfed many northern and central towns. Many people said they feared reprisal violence.

Ethnic tensions have long existed in Mali, and inter-communal violence has erupted in the past, but an October study by Oxfam revealed that the 2012-2013 conflict frayed (pustede ild til) social relations more profoundly than previous violence.

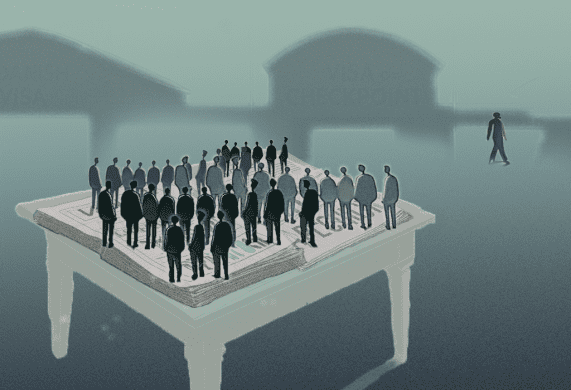

“A strong fear to return home”

“There is this overall feeling that there has been a major degradation of social relationships,” said Steve Cockburn, Oxfam’s West Africa campaigns and policy manager. “There is quite a strong fear to return home.”

He told IRIN that some of the displaced and the refugees “feared that there would be tensions and conflicts within the community, that there would not be a lasting peace, and that they would have to leave again in the near future.”

Beyond the recent conflict, longstanding poverty, corruption, and anger over underdevelopment, marginalization and injustice in northern Mali are seen as factors undermining social relations, Oxfam said.

“In a broader reconciliation process, how does the Malian state devise a process that brings those dissenting voices in?” asked Cockburn.

He said many of the study’s respondents expressed a lack of faith in state institutions and showed more confidence in traditional mechanisms of governance.

“Reconciliation programmes will have to be at the community level. It is less about political agreements at the high level and more about being able to share tea with your neighbour. Will your friend pick up your call? Will you be able to take your cattle to a trader?”

Mistrust

The collapse of social cohesion (social sammenhæng i samfundet) is visible in the tendency to generalize blame.

Sixty percent of respondents who believe that social relations have worsened blamed whole ethnic groups rather than individuals, said Oxfam’s report, which also noted that threats, violence and stigmatization (social udstødelse) have contributed to the strained relations.

“Houses belonging to Arabs and Tuareg suspected to have colluded (samarbejdet) with the MNLA [the Tuareg National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad] and the MUJAO [Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa] were looted (plyndret). At times, there was no distinguishing whether they collaborated with the rebels or not. As long as you have light skin, you were targeted,” said Youssouf Traoré.

He works for the Gao-based Association of Sahel Agricultural Advisors (ACAS), a partner organization of International Organization for Migration (IOM) that supports the tracking of returnees.

Mistrust is highest among the displaced, who have undergone the hardships of fleeing and living in refuge. For some, it is not the first time they have been forced from their homes, said Oxfam’s Cockburn.

Going home?

Læs videre på

http://www.irinnews.org/report/98987/mali-conflict-inflames-ethnic-tensions