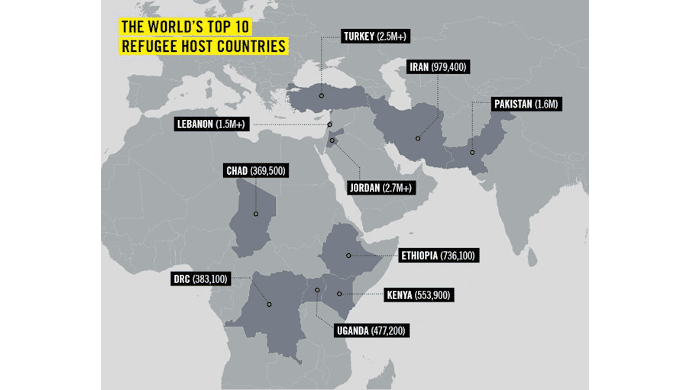

LONDON, 4 October 2016 (Amnesty intl.): Wealthy countries have shown a complete absence of leadership and responsibility, leaving just 10 countries, which account for less than 2.5% of world GDP, to take in 56% of the world’s refugees, said Amnesty International in a comprehensive assessment of the global refugee crisis published today.

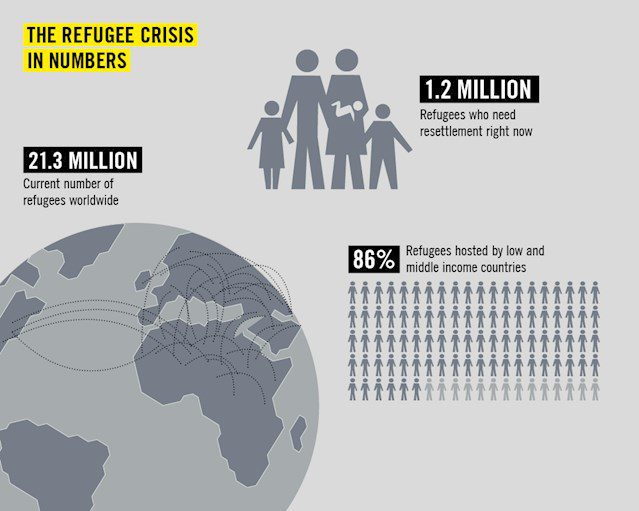

The report Tackling the global refugee crisis: From shirking to sharing responsibility, documents the precarious situation faced by many of the world’s 21 million refugees.

While many in Greece, Iraq, on the island of Nauru, or at the border of Syria and Jordan are in dire need of a home, others in Kenya and Pakistan are facing growing harassment from governments.

The report sets out a fair and practical solution to the crisis based on a system that uses relevant, objective criteria to show the fair share every state in the world should take in in order to find a home for 10% of the world’s refugees every year.

“Just 10 of the world’s 193 countries host more than half its refugees. A small number of countries have been left to do far too much just because they are neighbours to a crisis. That situation is inherently unsustainable, exposing the millions fleeing war and persecution in countries like Syria, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Iraq to intolerable misery and suffering,” said Amnesty International Secretary General Salil Shetty.

“It is time for leaders to enter into a serious, constructive debate about how our societies are going to help people forced to leave their homes by war and persecution. They need to explain why the world can bail out banks, develop new technologies and fight wars, but cannot find safe homes for 21 million refugees, just 0.3% of the world’s population.”

“If states work together, and share the responsibility, we can ensure that people who have had to flee their homes and countries, through no fault of their own, can rebuild their lives in safety elsewhere. If we don’t act people will die, from drowning, from preventable diseases in wretched camps or detention centres, or from being forced back into the conflict zones they are fleeing.”

Refugees across the world in dire need

The report underlines the urgent need for governments to increase significantly the number of refugees they take in, documenting the plight of refugees on all continents:

Sent back to conflict zones and human rights violations

- Growing numbers of refugees in Pakistan and Iran are fleeing Afghanistan in the face of an intensifying conflict. Afghan refugees in Pakistan face increasing harassment from the authorities, who have already forced more than 10,000 to return to their war-torn country.

- In Kenya, refugees living in the Dadaab camp are facing pressure to return to Somalia. The government wants to reduce the size of the refugee camp’s population by 150,000 people by the end of 2016. More than 20,000 Somali refugees have returned to Somalia from Dadaab.

- More than 75,000 refugees fleeing Syria are currently trapped at the border with Jordan in a narrow stretch of desert known as the berm.

Kept in dire conditions

- In Southeast Asia, Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers from Myanmar live in constant fear of arrest, detention, persecution and in some cases refoulement. In detention centres in Malaysia the Rohingya and other refugees and asylum-seekers endure a range of harsh conditions, including overcrowding, and are at risk of disease, physical and sexual abuse, and even death due to lack of proper medical care.

- The report accuses some EU countries and Australia of using “systemic human rights violations and abuse as a policy tool” to keep people out. In July 2016, Amnesty International found that the 1,200 women, men and children living on Australia’s offshore detention centre on Nauru suffer severe abuse, inhumane treatment, and neglect.

- The EU is pursuing dodgy deals to limit flows of refugees and migrants with Libya and Sudan, amongst others. Refugees suffer widespread abuses in immigration detention centres where they are held unlawfully, without access to lawyers, following their interception by the Libyan coastguard or detention by armed groups and security officers. The security forces Sudan uses to control migration have been associated with human rights abuses in Darfur.

Forced to take dangerous journeys

- From January 2014 to June 2015, UNHCR recorded 1,100 deaths at sea in Southeast Asia, mostly of Rohingya refugees, although the number of deaths is likely to be much higher.

- In 2015 more than one million refugees and migrants reached Europe by sea, with almost 4,000 feared drowned. More than 3,500 fatalities have already died in the first nine months of 2016.

- In 2016 women refugees from sub-Saharan Africa who had passed through Libya told Amnesty International that rape was so commonplace along the smuggling routes that they took contraceptive pills before travelling to avoid becoming pregnant as a result of it. Refugees and migrants have reported that people smugglers hold them captive to extort a ransom from their families. They are kept in deplorable and often squalid conditions, deprived of food and water and beaten.

- Refugees and asylum-seekers fleeing growing violence in Central America’s Northern Triangle have faced kidnappings, extortion, sexual assault and killings during the journey through Mexico towards the US border.

“The refugee crisis is not limited to the Mediterranean. All over the world refugees lives are at risk, crammed into packed boats, living in abject conditions and at risk of exploitation, or taking dangerous journeys where they are at the mercy of smugglers and armed groups. World leaders must work out a fair system to share the responsibility for helping them,” said Salil Shetty.

Countries neighbouring conflicts left to shoulder vast majority of world’s refugees

The report says that unequal sharing of responsibility is exacerbating the global refugee crisis and the many problems faced by refugees. It calls on all countries to accept a fair proportion of the world’s refugees, based on objective criteria that reflect their capacity to host refugees.

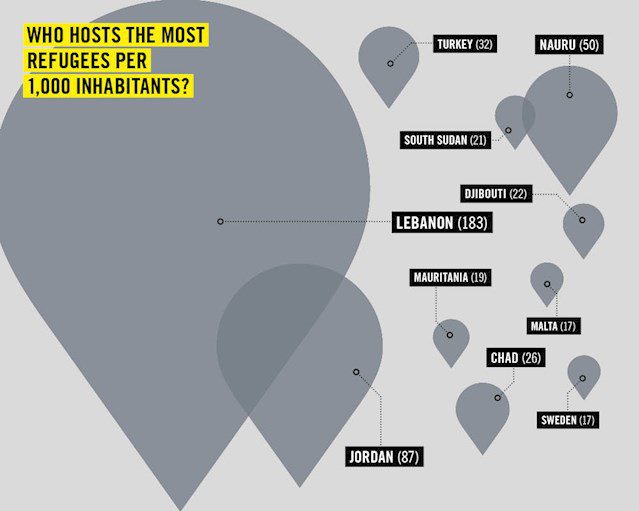

The report says a basic common-sense system for assessing countries’ capacity to host refugees, based on criteria like wealth, population and unemployment, would make it clear which countries are failing to do their fair share.

The report highlights the stark contrast in the number of refugees from Syria taken in by its neighbours and by other countries with similar populations.

- For example, the UK has taken in fewer than 8000 Syrians since 2011, while Jordan – with a population almost 10 times smaller than the UK and just 1.2% of its GDP – hosts more than 655,000 refugees from Syria.

- Lebanon, with a population of 4.5 million, a land mass of 10,000km2 and a GDP per capita of US$10,000, hosts over 1.1 million refugees from Syria , while New Zealand with the same population but a land mass of 268,000km2 and a GDP per capita of US$42,000 has only taken in 250 refugees from Syria to date.

- Ireland, with a population of 4.6m, a land mass seven times bigger than Lebanon and an economy five times larger, has so far only welcomed 758 refugees from Syria.

The report shows how the richest countries in the world could take a fairer share of the current world population of vulnerable refugees. For example, using the criteria of population size, national wealth and unemployment rate, then New Zealand would take in 3,466. These are eminently manageable numbers, when contrasted against the 1.1 million UNHCR-mandate refugees in Lebanon, with its similar population.

“The problem is not the global number of refugees, it is that many of the world’s wealthiest nations host the fewest and do the least,” said Salil Shetty.

“If every one of the wealthiest countries in the world were to take in refugees in proportion to their size, wealth and unemployment rate, finding a home for more of the world’s refugees would be an eminently solvable challenge. All that is missing is cooperation and political will.”

(Tal fra 2015)

Foto: Amnesty International

More governments must show leadership

The report cites Canada as an example of how, with leadership and vision, states can resettle large numbers of refugees in a timely manner.

Canada has resettled nearly 30,000 Syrian refugees since November 2015. Slightly more than half were sponsored by the Canadian government, with close to 11,000 others arriving through private sponsorship arrangements. As of late August 2016, an additional 18,000 Syrians’ applications were being processed – mainly in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

Today only around 30 countries run some kind of refugee resettlement programme, and the number of places offered annually falls far short of the needs identified by the UN. If this increased to 60 or 90, it would make a significant impact on the crisis, the report said.

To encourage more countries to take effective action, Amnesty International is calling for a new mechanism for resettling vulnerable refugees and a new global transfer mechanism for acute situations like the Syrian conflict, so that neighbouring countries would no longer be overwhelmed when large numbers of people flee for their lives.

“The world cannot go on leaving host countries overwhelmed because they are next to a crisis country with no support from the rest of the world. While a small number of countries host millions of refugees, many countries provide nothing at all,” said Salil Shetty.

“World leaders have completely failed to agree a plan to protect the world’s 21 million refugees. But where leaders fail, people of good conscience must increase the pressure on governments to show some humanity towards people whose only difference is that they have been forced to flee their home.”

(Tal fra 2015)

Foto: Amnesty International

The figures in the report are based on UNHCR and UNRWA figures, as well as government and NGO figures where relevant.

Download rapporten Tackling the global refugee crisis: From shirking to sharing responsibility

Tackling the global refugee crisis: From shirking to sharing responsibility