When I last wrote about Ugandan domestic politics, the February 2016 presidential election was still six months away. The big news was that Amama Mbabazi – the former prime minister – was running.

Mbabazi had been sacked by President Museveni the year before and was seeking to forge an opposition ticket from an ambiguous position, not quite in and not quite out of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM).

Mbabazi told me that his candidacy was “the biggest ever threat to Museveni’s leadership”. This seemed fanciful, and it was unclear whether a third figure on the normally polarised political scene would break open the competition. Would there be a crumbling of consensus within the ruling elite? If so, would it threaten the country’s internal stability?

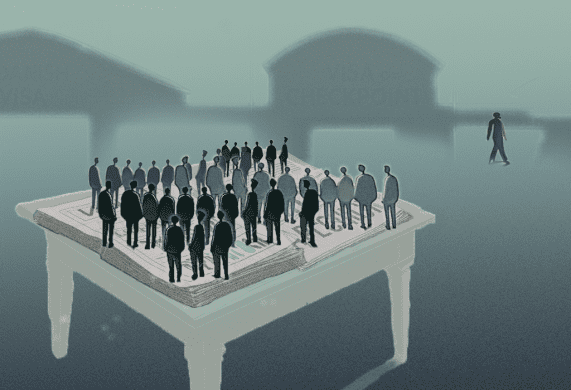

Now, ten months on, the answer is clear. Not yet. Museveni won comfortably with 61.8 per cent of the vote. But something else might still unsettle the status quo. Museveni spent a lot of time and resources fighting Mbabazi. In doing so, did he take his eye off his opponent for the last four elections, Kizza Besigye?

Post-election Tensions

Besigye won 35 per cent and made considerable advances in urban areas – particularly Kampala (an opposition stronghold), but also Mbale in the east, Fort Portal in the west and Gulu in the north. This spooked the NRM, which decided that the best way to deal with the threat of post-election anti-government demonstrations was to keep Besigye under house arrest.

The NRM clearly understands it faces a big challenge in containing political opposition in the five years before the next polls. Overcoming that challenge will require more creative political solutions than current hard-fisted attempts to shut down the operations of serious opposition.

Læs hele analysen hos International Crisis Group