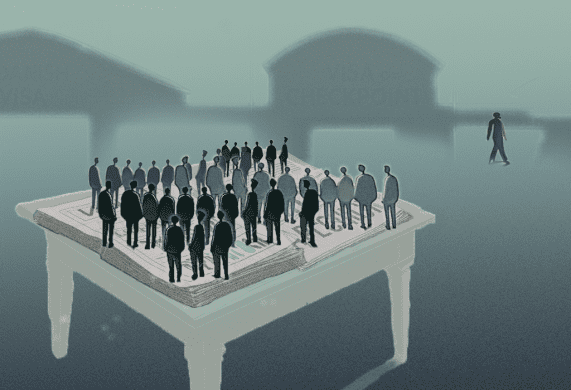

Donorernes holdning til Uganda er primært formet af een ting: Deres opfattelse af præsident Museveni selv. De håbede, at han ville lede en demokratisk proces. Deres skuffelse illustrerer de vanskeligheder og valg, som donorer møde i Afrika.

Donors’ attitudes to Uganda have gone through a number of phases. One key element in forming the donors’ attitudes has been President Museveni himself and the shifting ratings of his person and policies.

A major difference in constituting the donors’ opinion is between on the one hand the economic policy and the economic performance of the country and on the other hand the situation and changes within the political arena.

Over the years the overall picture is that the donors’ attitudes have differentiated and have changed considerably towards a more critical and even negative opinion possibly culminating in some kind of crisis over recent years

The path towards democracy

The period 1989 – 1996 represents crucial events in deciding the future political system in Uganda and important steps on the path towards democracy.

It covers the setting-up of the Constitutional Commission in 1989, the election to the Constituent Assembly in 1994, the approval of the new constitution in 1995, and the presidential and parliamentary elections in 1996.

It also represents one of the first experiences of the donor community being solidly involved in support and guidance for the transition to democracy.

At this first stage there was limited donor coordination. The various donors were acting very much on their own. The EU for instance did not yet have the capacity and authority to coordinate its own members.

Denmark was a lead donor in three important areas: the Constitutional Commission, the Electoral Commission (primarily by supplying electoral experts and observers), and not least the important area of decentralisation which ran parallel to the constitution-making and constituted a central element in the whole process of democratisation.

The Movement system

The crucial issue for donors was the introduction of the Movement system with its restrictions on the activities of political parties. It questioned the essence of democracy, and donors were inclined to equate the no-party system with the familiar one-party system.

But over the period the pendulum swung towards the broader definition of democracy. Most donors and not least Danida focused on guarantees for pluralism and for fair play in the election campaigns.

As the three elections were conducted with no more flaws than could be expected most donors ended up accepting the no-party system.

Some of the major donors like Germany, Britain and the US came at certain times with critical outbursts demanding an introduction of a proper multi-party system, but in the end they acquiesced with the no-party system written into the new Constitution.

There were mixed motives involved both in general and for the individual donors. Both economic, strategic and pragmatic considerations played a role thereby reducing the emphasis on democracy as the only factor of importance.

The strategic considerations did not only include external relations, in casu to Sudan, but also the internal peace and tranquillity.

The Movement system as administered by President Museveni was at this particular juncture in Uganda’s development seen as the best way to bridge the many cleavages in Ugandan society, mainly of ethnic and religious origin, but also the divisions stemming from the bad record of the old political parties since independence.

Democratic practices

It was, however, a limited and conditional acceptance of the Movement system and not a fully fledged endorsement.

For most donors the no-party system represented a democratic deficit. But many donors, not least the Danes, included in their assessment some additional factors which compensated for the deficit.

One was the democratic practices included in the whole constitution-making process. Another and very important factor was the far reaching decentralisation process which was a key element in the new political dispensation under Museveni and written into the Constitution as the key principle along with the empowerment of women.

Besides the element of pragmatism two other points were of special importance for the donors during this first period.

First, the donors’ endorsement of the Movement system was to a large extent based on the high regard in which they held President Museveni, and the trust they had in him as a true follower of basic democratic principles.

Secondly, the donors accepted the Movement system as a temporary measure adapted to the special circumstances in a period of transition.

Museveni and his army

During the following period 1996-2001 ending with the referendum in 2000 and the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2001 these two areas, the trust in Museveni and the future of the Movement system, were decisive for an understanding of the hardening of the donors’ attitudes.

With regard to the first one, the Museveni factor, his position as ‘the darling of the donors’ was declining both because of his more autocratic style and his increasing unwillingness to listen to adverse arguments and engage in dialogue.

He even criticised donors for not doing enough, for doing the wrong things and for their repeated ‘advice’ on best democratic practices.

The continued insurgency in the North on the border to Sudan and not least the involvement in the crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo left the impression of increasing reliance and dependency on the military.

In addition events within the army and in other parts of the public sector brought various malpractices like huge corruption into the open.

The increasing scale of these malpractices left the impression that Uganda had not grown out of the neo-patrimonial practices. A number of cracks appeared in the otherwise promising process towards good governance at a time when this issue figured higher on the donors’ agenda.

All these things contributed to wrecking the earlier, generally positive image of Yoweri Museveni.

Unhappy with democratic deficit

With regard to the second area, the Movement system and its restrictions on the activities of political parties, the donors were still, although in varying degrees, unhappy with the democratic deficit it represented.

Eventually the donors acquiesced with the continuation of the Movement system which was the outcome of the referendum in 2000, not least because it fully respected the constitutional provisions.

Instead they focused on the need for a level playing field during the electoral processes and expressed great concern about the increasing violence connected with the campaign to the 2001 elections and the growing involvement of the military.

They had great doubts about the outcome of the presidential election where Yoweri Museveni polled 69 percent of the votes against his opponent, Col. Besigye who got about 28 percent but they left it to the court system to decide on the whole electoral process.

The Supreme Court vindicated the result of the election, but in its ruling it pointed to severe shortcomings and the need for improvements of the whole procedure.

One consequence was that the Electoral Commission with one exception was sacked, one reason simply being cases of corruption.

The donors officially accepted the outcome of the election in spite of criticism of parts of the process and misgivings about the high degree of violence and not least the interference of the military.

Two motives seem to have driven most of the donors. The first one was the pragmatic one that after all Yoweri Museveni was the best card in the situation, that he would secure the continued economic growth, and that he was the best to control the army, not least in view of their visibility during the election process.

The second motive was that after all the whole exercise with referendum and elections respected and followed the constitutional prescriptions. Every thing had been carried out on constitutional ground.

Following the last argument the donors consoled themselves that in accordance with the Constitution President Museveni could only hold office for two terms thus calling attention to the fact that the second term would be the last one and that there was a need for looking into the question of succession.

Donors unite

One first impression of the donors’ attitude during the period up to 2001.is that they are fairly acquiescent and as long as certain democratic rules and behaviour are respected they are prepared mainly for pragmatic reasons to give leeway for the unfolding of the political processes on President Museveni’s terms.

This seems in general to be the acceptable, common denominator, but it covers a variety of opinions and even disagreements about the line to follow vis-a-vis the Ugandan government.

One significant feature is the new development of an organisational pattern among the donors clearly aimed at unifying the attitudes and acting with a stronger voice vis-a-vis the government.

Two fora were sparked off by the prevailing uneasiness with the lack of pluralism.

The first forum was the EU countries. They are supposed to inform each other and not least coordinate their aid activities. They hold regular meetings at short intervals, but when it comes to political matters they are often hampered by internal disagreements and are in many ways not a homogenous group that can act with one common voice.

Another forum was started among like-minded donors. In connection with the referendum in 2000 they formed a monitoring committee with most EU countries as the core group, but also including the US, in order to create a strong and broad based donor forum. Denmark became the chairman and spokesperson.

This donor forum expanded its membership also to include important donors like Japan, Canada and Norway, and also UNDP joined. The forum – now called PDG (Partners for Democracy and Development) has during the years achieved the status as the authoritative spokesman for the most important donors and is acknowledged by the President and the government as such.

Invasion in DR Congo

The different approaches to Uganda’s record of democracy and good governance were put to a test in connection with the Ugandan involvement in the Congo turmoil and the Ugandan army’s clash with Rwanda in the late 1990s.

On that occasion Denmark went on its own and gave absolute priority to good governance. Contrary to other donors it dispensed with all other explanations and wider concerns like security and saw the involvement in Congo as an outright invasion, violating all rules and principles for the relationship between nation states.

The devastating criticism of Uganda’s exploitation of Congo’s rich resources contained in the first UN report about the crisis in the Great Lakes Region was endorsed by most political parties in Denmark.

Cut in Danish aid

The Danish government was the only donor to take the full consequences and make cuts in its aid to Uganda by cancelling all budget support.

It coincided with the Danish election campaign in the last half of 2001 during which the invasion of Congo combined with the peculiar no-party system and strong criticism of Museveni’s leadership became an issue.

When a liberal-conservative government came to power in November 2001 it seriously considered pulling out of Uganda entirely. In the end it stopped short of that and made a ten percent cut in aid to Uganda.

In the end Uganda was ‘rescued’ by its generally good performance in using aid money, by its determination to address the poverty issue and by its sound economic policy.

But it was just as important that at the decisive moment there were other countries with an even worse record with regard to democracy and good governance so in the end Denmark decided to pull out entirely from Zimbabwe, Malawi and Eritrea.

Donor pressure for pluralism

After the 2001 presidential election with its malpractices, violence and involvement of the army the donors revised their agenda, and three issues came at the top.

First, within the area of good governance they sought to strengthen the electoral procedures by supporting the electoral commission and its improvement of the voters’ register, to strengthen the judiciary and to support relevant institutions in fighting corruption.

Secondly, they criticized the government and the army for inefficiency and unnecessary violations of the local people’s rights in fighting the LRA and its atrocities, and they made special efforts to address the general negligence of the North.

Thirdly and not least they strengthened the argument for finally bringing the transition period to an end and introduce a proper multi-party system.

The latter issue was the politically most sensitive, but also the area where the donors were most determined to get a change of the system.

The President found the change much too early and pointed to well known evils from the earlier multi-party era. But the donors found a positive response from some of the cabinet ministers and from a number of MPs.

The Third Term

The pressure started to build up when another issue gradually appeared on the agenda. To the surprise of most donors the issue of a Third Term for President Museveni was introduced with his approval although he officially put his own candidature in the uncertain darkness.

The Third Term issue sparked off a major division within the ruling NRM. A number of the leading personalities protested and either separated themselves from the NRM or were excluded.

Some of them went into the political wilderness, while others linked up with the Reform Agenda and prepared for the new party, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). This meant a greater upheaval within the Uganda political arena than seen for a long time.

Take it or leave it

These changes were masterminded by the President, and the message to the donors was quite clear: you get your long wanted multi-party system against my wishes, but the price you have to pay is the Third Term. We cannot do both in one stroke. The Movement system will go, and the NRM will transform itself to a political party alongside other parties, but the succession issue will not be part of the packet and will postponed to an undefinite time in future.

This link between the multi-party system and the Third Term issue took the donors by surprise. The obvious trade-off between the two was a highly divisive issue and put the PDG into a serious dilemma.

Eventually things rolled on, and in the middle of 2005 the multi-party system was in accordance with the Constitution approved in a referendum, while the limit on presidential terms was abolished by a majority vote in Parliament.

Deep divisions among donors

From there on there were deep divisions among the donors, the crucial issue being whether sanctions should be introduced or whether the usual pragmatism in the end should prevail making the best out of the pluralism that finally had been introduced.

First among the hardliners was Britain. The Minister for Development, Hilary Benn, decided to make a cut in the amount earmarked for budget support. Soon after it transpired that the reduced amount came from the promised growth in the aid volume, not a direct cut.

And shortly after the British Minister made some conciliatory remarks by stating that the changes were made on constitutional grounds, and that Britain would take a longer term view of developments in Uganda. In the end Britain took a more flexible approach and moved away from the hardliners.

Norway (not an EU country) was the next to announce a twenty percent cut in the aid volume, again in the budget support and not in the aid programme.

Ireland and Holland had followed suit again by cutting in budget support or diverting their means to other aid programmes in Uganda, and Sweden was close to do the same. There was no joint action by the EU as such. The typical response, however. was to make cuts in budget support, but not to do any harm to the programmes up country.

This again enabled the President and ministers to belittle the sanctions and criticise the donors for undue interference. After all the government had acted on constitutional ground.

Most important: Multi-party system

Most other donors in the PDG took a different attitude, in the first place by confining themselves to verbal protests, some of them with fairly strong wordings. As the long standing Chairman of the PDG, Denmark’s position is of special interest.

While the Danish ambassador tried to keep as much unity as possible among the donors he was in his approach guided by two considerations.

First, Denmark made great effort to reduce the alternative between multi-party and Third Term. This pragmatic approach prevailed, so instead of a continued battle against Third Term with little chance of success it would be better from the Danish point of view to get the multi-party system to work first and foremost by securing a level playing field with equal rights for all political parties, and put the Ugandan government to test on that ground.

The second element in the Danish position was an increasing doubt and a change of attitude to sanctions by cuts in the aid budget such as Denmark had practiced during the Congo crisis mentioned above. The experience was that such sanctions rarely worked, but rather hit poor people unfairly and not the people in power.

Denmark also argued for the need for more patience with regard to the democratisation process and not just jump to the usual fire brigade approach.

Eventually the Danish position of making the best out of the situation and work for continued progress within one area became the generally accepted formula within the donor group.

Misuse of the court system

The donors followed closely and supported the procedures for the coming elections and the election campaign. They put a lot of effort into securing a level playing field, for instance with regard to access to the media, protests against violations of the independency of the media and the incumbent’s and his new party’s use of public funds – like they were used to in the good old Movement days!

The culmination came when the leading opposition candidate and representative for the new party, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), Dr. Kizza Besigye was arrested soon after his return from exile and charged with rape, treason, attempts at terrorism and illegal arms possession.

This could only be seen as a deliberate attempt to use the courts in the election campaign, and the situation became even worse when Besigye also appeared before a General Court Martial, which meant that he should be tried simultaneously by a civilian and a military court.

The donor representatives took a strong stand by being present at the High Court In Toto, and they protested in general against the misuse of the court system and against the military’s attempt to interfere in the judicial procedures.

The election campaign did not present a rosy picture, and it reflected badly on the Museveni regime and raised doubt about his real commitment to bring the multi-party system into practice.

The violence and military interference, however, were absent in marked difference from the situation in 2001.

A new start in 2006?

Is there a new situation after the elections with a new agenda? Some of the donors have invested a lot in the multi-party system, and for them it will be important that it works and is strengthened in the future.

On the one hand the omens are not too good. The NRM has an overwhelming majority in Parliament and can rule without the opposition.

As long as the democratic culture is still at the initial phase there can also be a return to a previous practice that members of the opposition parties are ‘bought’ and start to cross the floor. The great number of so called independents in Parliament can start the ball rolling.

The government can also choose to neglect Parliament as to a large extent it has done with the previous parliament. And measured by its celebrations and vigilant language there seems to be little willingness to reconcile and get democratic procedures to work.

On the other hand, the multi-party democracy has worked and the people have shown their support for it by turning out in great numbers. Parliament is preparing to give the opposition its proper place. A new configuration of the multi-party system has appeared.

The new party FDC has established itself remarkably quickly, and compared to the old and now reduced parties, DP and UPC, it is a nationwide party lifted out of ethnic and religious affiliations.

The situation for the parties may change even further as the NRM according to some analysts may over time break up into factions, not least in connection with the inevitable succession question.

Pragmatism and investments

This latter scenario may be wishful thinking for some of the donors. The important question now is which agenda the donors will set up. They have got an imperfect multi-party system, and the question is whether they will keep this highly politicised issue on the agenda under the new circumstances.

It is still early days, but some of the donors have not forgotten the issue of Third Term. It is interesting that the head of the EU observer group after the endorsement of the elections on 23 February 2006 added that Uganda ought to return to the earlier two terms limit.

Some of the hardliners among donors have still a very critical attitude to the Ugandan development, but big countries like the US and the UK take a broader view of the situation, for instance by including a strategic assessment of Uganda’s position regionally and internationally.

For some donors strategic considerations count for more than pure democratic practices within Uganda. And possibly some of the big donors look at their investments in the country over a long span of years.

Or as the Danish Ambassador remarked: It is a question of confrontation with Museveni or dialogue with him.

————-

Holger Bernt Hansen var i marts 2006 inviteret til udenrigsministeriet i Washington for at tale om ”Uganda and the Donors´Crisis of Confidence.” Ovenstående er en beskåret udgave af hans fremlæggelse.

Holger Bernt Hansen er professor, dr.phil og ikke kun Danmarks mest fremtrædende Uganda-kender, men internationalt anerkendt Uganda-forsker og specialist. Han har publiceret bredt om Uganda. Han var formand for Danidas styrelse fra 1996 til 2007.