Naturmæssige forbrydelser, f.eks. krybskytteri, ligger langt nede på politiets prioriteringsliste. Men senest med terrorangrebet i Nairobi er emnet rykket op ad listen, da gruppen bag angrebet menes at få 40 % af sin indtægt fra elefant-krybskytteri.

NEW YORK, 3 October 2013 (IRIN): Organized environmental crime is known to pose a multi-layered threat to human security, yet it has long been treated as a low priority by law enforcers, seen as a fluffy “green” issue that belongs in the domain of environmentalists.

But due to a variety of factors – including its escalation over the past decade, its links to terrorist activities, the rising value of environmental contraband and the clear lack of success among those trying to stem the tide – these crimes are inching their way up the to-do lists of law enforcers, politicians and policymakers.

The recent terror attack on the popular Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi, Kenya, has placed environmental crimes like the ivory and rhino horn trade under increased scrutiny.

Al-Shabab, the Islamist militant group that has taken credit for the attack, is widely believed to fund as much as 40 percent of its activities from elephant poaching, or the “blood ivory” trade.

The Lord’s Resistance Army, a brutal rebel group active in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic, is also known to be funded through elephant poaching.

Rising incomes in Asia have stimulated demand for ivory and rhino horn, leading to skyrocketing levels of poaching. Over the past five years, the rate of rhino horn poaching in South Africa has increased sevenfold as demand in Vietnam and other Asian countries for the horn – used as cancer treatments, aphrodisiacs and status symbols – grows.

“Drop in the ocean”

On the international stage, politicians – alarmed by increasing evidence of links between terrorist organizations and organized environmental crime – are taking a more visible stand against wildlife trafficking. In July, US President Barack Obama set up a taskforce on wildlife trafficking and pledged US$10 million to fight it.

But this is a mere “drop in the ocean”, says Justin Gosling, a senior adviser on environmental organized crime for the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, which was recently launched in New York.

“If developing countries really want to assist, they need to put up quite a bit of cash,” he added.

Funded by the governments of Norway and Switzerland, the Global Initiative is a network of leading experts in the field of organized crime, which aims to bring together a wide range of players in government and civil society to find ways to combat illicit trafficking and trade.

At the Global Initiative conference, Gosling presented a draft of The Global Response to Transnational Organized Environmental Crime, a report documenting environmental crimes around the world. Such crimes are on the rise in terms of “variety, volume and value”, the report says, and their impact is far greater than the simple destruction of natural resources and habitats.

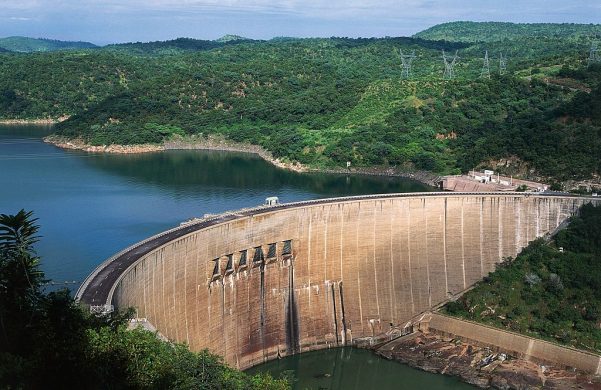

“They affect human security in the form of conflict, rule of law and access to essentials such as safe drinking water, food sources and shelter,” the report says.

The crimes documented range from illicit trade in plants and animals and illegal logging, fishing and mineral extraction to production and trade of ozone-depleting substances, toxic dumping, and “grey areas” such as large-scale natural resource extraction.

Most vulnerable

The most fragile countries – those lacking infrastructure and effective policing but often rich in untapped natural resources – are the most vulnerable to exploitation, and the poorest communities suffer the most.

“For millions of people around the world, local reliance on wildlife, plants, trees, rivers and oceans is as strong as it has ever been,” says the report.

Communities are losing food supplies and tourism jobs through unsustainable hunting, fishing and – often illegal – deforestation. In vulnerable countries like the Maldives, for example, populations are at risk from rising sea levels and climate change brought on, in part, by deforestation.

It is impossible to quantify what proportion of organized crime is environmental crime, although 25 percent is a commonly repeated figure.

This number comes from a UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimate of the scope of the problem in the Asia-Pacific region, and it is often extrapolated as a global estimate.

Even less is known about how much organized environmental crime drains from the legitimate economy.

To complicate matters, the line between environmental and other organized crime is often blurred, since the same trafficking networks are frequently used for both.

“We’re not really trying to look at environmental organized crime in terms of value,” said Gosling.

“We’re looking at the global response to the problem. Who are the actors, and what are they doing? Is it sufficient, and if not, what can we do?”

Boosting enforcement

Læs resten af artiklen: http://www.irinnews.org/report/98872/environmental-crimes-increasingly-linked-to-violence-insecurity