ALI ADDEH, Djibouti, 15 December, 2017 (UNHCR): Crowds of hundreds of excited refugees welcomed the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi as he arrived at the dusty, remote Ali Addeh refugee camp in the desert of southern Djibouti.

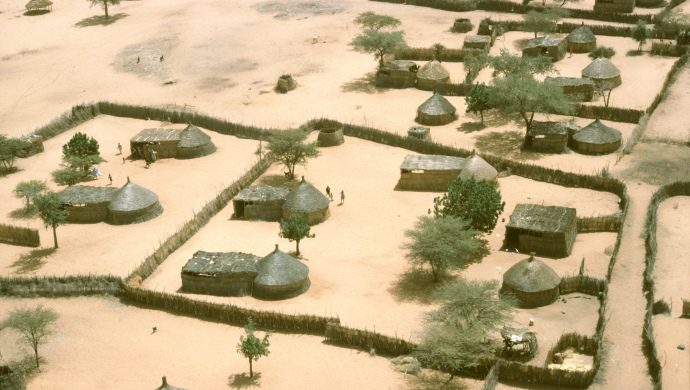

The camp, established at the start of the Somalia conflict in 1992, is home to more than 15,000 Somali refugees, many who were born there.

“Life in the camp is very tough and it is difficult to find enough water and food for my family,” Amina Ahmed Ali told Grandi, seated in her basic one-room hut lined with mattresses but no furniture. Seven children share the space with her and her husband; three of their own, four whom they foster. Planting is impossible in the dry, saline soil and she has to rely on monthly World Food Programme rations and some occasional additions bought with her small salary from her social work in the camp.

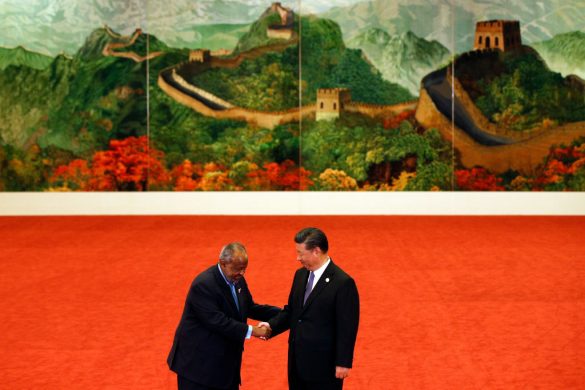

The High Commissioner praised Djibouti’s generosity in taking in over 27,000 refugees from four neighboring countries. He applauded the government’s announcement yesterday that all refugee camps in the country will now be considered villages.

“This is extremely important as it means that refugees will have freedom of movement and can access public services and whenever possible, jobs,” said Grandi.

“Djibouti has always been a very open country, but the fact that they announced it and this follows some very progressive legislation that the country has been issuing in the last few months, is extraordinary.”

Yesterday, the High Commissioner attended the Regional Education Conference hosted by the eight Eastern Horn African countries in a body called the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). At the conference, the countries, including Djibouti, agreed to integrate refugees into national education systems, and eventually receive certificates that are recognised throughout the region.

“This is so important because it recognizes that education is not just a right,” said Grandi, “but also an instrument of dignity and identity and also a very important investment to the future.”

The Government of Djibouti has already introduced a new education system that will allow refugees to study in English and adapt quickly to the Djiboutian curriculum. In Ali Addeh, students in Grade One are already learning the new syllabus.

Angosom Tesfu, a Math and English teacher of Grade one students at Wadajir pre-primary school, echoed the High Commissioner’s sentiments. He noted that the new curriculum is a progressive strategy that will create opportunities for refugees in Djibouti.

“Education is the key for everything especially in the era we live in today,” he said. “As long as these children are living here, it is important that they learn the Djiboutian curriculum as one day they can get valid certificates.”

Grandi also commended Djibouti for honoring pledges he made at a Leader’s Summit at the UN last year and for taking the part in the so-called Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework by passing progressive laws.

Djibouti currently hosts over 27,000 refugees, majority of whom are Somali.

“Djibouti is one of the smallest countries in Africa. It’s a country that has very limited resources, but is an example of generosity of visionary policies, and good management of refugee influxes,” said High Commissioner Grandi. “It is an example to the world.”