LONDON, 3 August 2015 (Amnesty International): Military police in Rio de Janeiro who seem to follow a “shoot first, ask questions later” strategy are contributing to a soaring homicide rate but are rarely investigated and brought to justice, Amnesty International said as it published exclusive statistics and analysis ahead of the one-year countdown to the 2016 Rio Olympic Games.

The report “You killed my son: Killings by military police in Rio de Janeiro” reveals that nearly 16% of the total homicides registered in the city in the last five years took place at the hands of on-duty police officers – 1,519 in total. Only in the favela of Acari, in the north of the city, Amnesty International found evidence that strongly suggests the occurrence of extrajudicial executions in at least 9 out of 10 killings committed by the military police in 2014.

To forskellige byer

“Rio de Janeiro is a tale of two cities. On the one hand, the glitz and glamour designed to impress the world and on the other, a city marked by repressive police interventions that are decimating a significant part of a generation of young, black and poor men,” said Atila Roque, Director at Amnesty International Brazil.

“Brazil’s failed ‘war on drugs’ strategy to tackle the country’s very real drug and violence public security crisis is backfiring miserably and leaving behind a trail of suffering and devastation. Too many lives are lost to the toxic cocktail of a corrupt violent and ill-resourced police force, communities so poor and marginalized they are hardly visible and a criminal justice system that constantly fails to deliver justice and reparations for human rights violations.”

Unødig og overdreven vold

According to Amnesty International’s research, military police across Rio de Janeiro has regularly used unnecessary and excessive force during security operations in the city’s favelas. The majority of victims of police killings registered from 2010 to 2013 are young black men of between 15 and 29 years of age.

Such killings are hardly investigated. When a person is killed as a result of police intervention, a civil police officer files an administrative report to determine if the killing was in self-defence or if a criminal prosecution is required.

In practice, many cases are filed as “resistance followed by death”, which prevents independent investigations and shields the perpetrators from the civilian courts.

By listing police killings as the result of a confrontation, even when there was never one, the authorities effectively blame the victims for their own deaths. This is often used as a smokescreen to cover up for extrajudicial executions. In cases where the police links the victim to criminal gangs, the investigation usually intends to support the testimony of the police that the killing occurred in self-defence instead of determining the circumstances of the homicide.

Amnesty International also found that crime scenes are frequently altered – police officers remove the body without due diligence and place weapons or other “evidence” next to the body. In cases where the victim is allegedly connected to drug trafficking, the investigation tends to focus on the victim’s criminal profile to legitimize the killing.

10-årig dræbt foran sit hjem

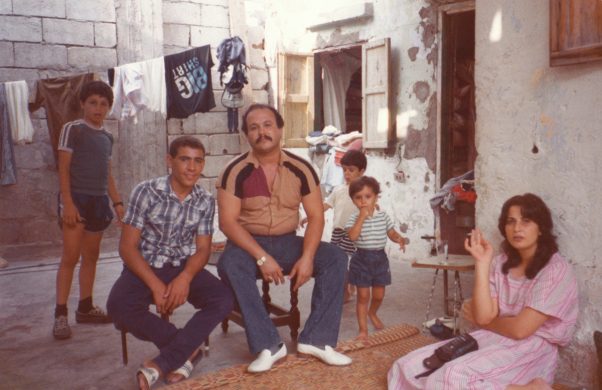

Eduardo de Jesus, 10, was killed by military police as he sat by his home door in the Complexo do Alemão favela on 2 April 2015.

According to his mother, Terezinha Maria de Jesus, 40, everything happened in a matter of seconds.

“I just heard a bang and a cry … When I ran outside I came across the horrible scene of my fallen son there,” she said.

When she confronted the row of military police officers standing in front of her son’s dead body, one of them pointed his rifle at her head and told her: “Just as I killed your son, I might as well kill you because I killed a bandit’s son”.

Terezinha said the crime scene was almost immediately dismantled by the police. They tried to take Eduardo’s body away but the community prevented them from doing it. One of the officers tried to place a gun next to the body to incriminate him.

The day after Eduardo’s death, the agents responsible for the shot that killed him were dismissed from the force and had their weapons taken for forensic analysis. The case is being investigated by the police force’s homicide division. But the reality is that most cases are not duly investigated and those responsible rarely face justice.

Since the killing, Eduardo’s family has received threats and were forced to move from their home for fear of reprisals.

“The military police’s strategy of fear when it comes to their operations in the city’s favelas, including harassing residents and threatening activists, will not resolve the city’s security problems. The only thing that will is a concerted strategy to reduce homicides and a guarantee that all human rights violations are thoroughly investigated and those responsible are brought to justice,” said Atila Roque.

Fakta

- Brazil has one of the highest number of homicides in the world: 56,000 people were killed in 2012.

- In 2012 more than 50% of homicide victims were aged between 15 and 29, and 77% of them were black.

- 8,471 cases of killings by police officers on duty were registered in the State of Rio de Janeiro, including 5,132 in the city of Rio de Janeiro between 2005 and 2014.

- The number of killing by on-duty police officers registered as “resistance followed by death” in the city of Rio de Janeiro represents nearly 16% of the total number of homicides in the city for the last 5 years.

- When reviewing the status of all 220 investigations of police killings opened in 2011 in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Amnesty International found that after four years, only one case led to a police officer being charged. As of April 2015, 183 investigations were still open.

Download rapporten You killed my son: Homicides by military police in the city of Rio de Janeiro (PDF, 47 sider)