After a four-hour-long trek from Bhojwasa, the final camping spot in Gangotri, we finally reached a brown pile of rocks .

It was hard to believe that this was the mouth of the glacier from which the holy Ganga emerged, high in the Himalayas in India’s Uttarakhand state.

Gaumukh, the snout of the Gangotri glacier, named after its shape like the mouth of a cow, has retreated by over 3 kilometres since 1817, says glaciologist Milap Chand Sharma of Jawaharlal Nehru University.

It was nearly two centuries ago that the retreat of the glacier was first documented by John Hodgson, a Survey of India geologist.

With ten Indian States reeling under drought and the country facing a severe water crisis after two weak monsoons, the disappearing freshwater sources such as the Himalayan glaciers is worrying.

And though a three-kilometre retreat over two centuries might seem insignificant at first glance, data shows that the rate of retreat has increased sharply since 1971. The rate of retreat is now 22 metres per year.

Less ice and snow

The glacier is in retreat because less ice is forming to replace melting ice every year, a process that is continuing, say scientists at the National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee.

“Winter precipitation is when the glacier receives adequate snow and ice to maintain itself. About 10-15 spells of winter snow as part of western disturbances feed the glacier. But last year Gangotri received very little snowfall. We have also observed more rainfall and a slight temperature rise in the region, both of which transfer heat on to the glacier, warming it,” Professor Manohar Arora, a scientist at NIH explained.

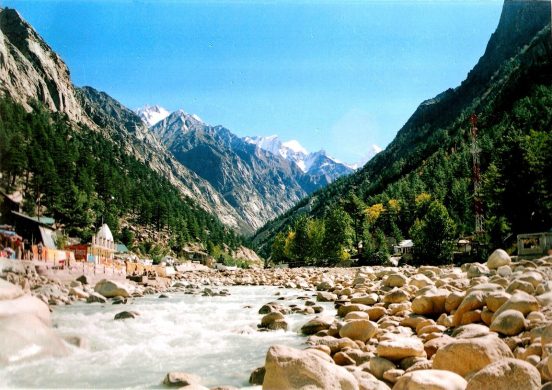

In summer, the melting glacier feeds the Bhagirathi River, the source stream of the Ganga.

A week ago, when this correspondent scaled 4,255 metres to reach the glacier, the day time temperature was about 15 degree Celsius, and the Bhagirathi was swollen with water.

However, dwindling snowfall has also reduced the volume of water (see chart below) in the river during the summer, compared to peak levels.

“Small lakes have formed on top of the glacier, as you go beyond Gaumukh towards Tapovan,” eminent conservationist and mountaineer, Harshwanti Bisht, who won the Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal in 2013, told The Hindu.

“It was the blast of one such glacial lake in Chorabari that led to the June 2013 flood disaster in Kedarnath,” she said, adding, “If such fast pace of melting continues, such disasters cannot be ruled out.”

Caving in under tourism and tree loss

Earlier the Gangotri glacier appeared as a convex shape structure from Tapovan, the meadow at the base of Shivling peak beyond Gaumukh, but now the glacier appears to be caving in, Bisht added.

“In 1977, when I used to go for mountaineering training, two or three cars could be spotted in Gangotri. But now there are hundreds and thousands of cars and buses plying pilgrims and tourists to these places during the summer months,” Bisht said.

“The Bhoj (birch tree) forests have disappeared in the region and though we are planting new trees now, their growth is very slow,” she said.

Since 1992, Bisht has been running a tree conservation programme “Save Gangotri” to help address the ecological crisis.

Irreversible melting

But the process of global warming and climate change could well be part of a normal natural cycle, Professor Milap Chand Sharma pointed out.

Reversing the process of retreat is impossible, he believes. “Stop people from visiting glaciers… you think this can happen… in India?” Sharma asked.

“Or else, increase solid precipitation (snowfall) during accumulation season [when the glacier grows]… or put a tarpaulin cover over the Himalayas during ablation period [when glaciers melt]…” he said.

In the end, if expert opinion is to be believed, the melting the glaciers could well be irreversible.

Artiklen er publiseret via en Creative Commons License på The Third Pole. Se den orginale artikel nedenfor.