The UN is defending its decision to revise how it measures chronic hunger, saying the change was needed to better reflect reality.

The revision has come under fire from academics, one of whom says the resulting statistics paint a “much-too-rosy trend picture”.

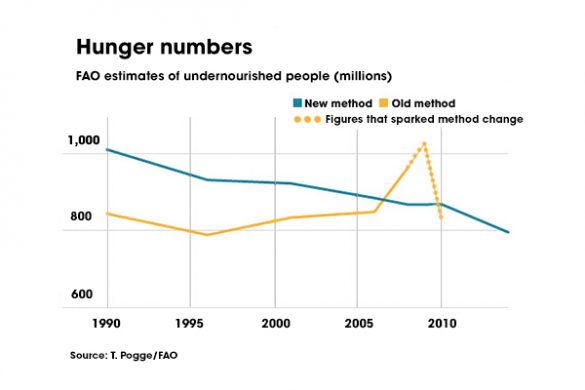

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) changed how it measures hunger in 2012. The previous method was tied to international food prices, which skyrocketed between 2008 and 2010, and showed hunger spikes that the FAO says did not reflect real life. The new method includes estimates of food production, trade, waste and distribution.

“The model used was based on the wrong presumption that everybody was facing food prices as high as those of international traded food commodities,” says Carlo Cafiero, an FAO statistician. He says the method failed to take into account government policies such as stopping food exports to protect consumers from soaring food prices.

Using the new method, the data shows hunger steadily falling over the past 25 years (see graph below). But not everyone buys the FAO’s conclusion that the proportion of hungry people has dropped by 21 per cent since the early 1990s, despite 1.9 billion extra people now living on the planet.

“The FAO’s new methodology vastly understates the number of chronically undernourished populations and people,” writes Thomas Pogge, a philosopher at Yale University in the United States, in a World Nutrition editorial published last month. His article is the latest in a series of criticisms levelled at the FAO’s method.

Pogge calls the FAO estimates “primitive” and “much-too-rosy”.

“It is bad practice to make so dramatic a change in methodology, with hindsight, in year 22 of a 25-year measurement exercise,” Pogge writes, referring to one of the Millennium Development Goals, which aims to halve chronic undernourishment between 1990 and 2015. He also says the FAO is under pressure from member countries who want more flattering numbers.

Although it stands by its numbers, the FAO acknowledges that having additional indicators would improve measurement of progress towards the upcoming Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ricardo Rapallo, a food security officer in the FAO’s office for Latin America and the Caribbean, says that using sampling studies as proposed by Pogge — covering, for example, body mass index, actual nutrient consumption and parasite prevalence — could improve hunger monitoring.

The SDG indicators are due to be finalised at a UN summit in March and then refined over the next two years, Rapallo adds. “We could have a battery of academically perfect indicators, but let’s be realistic” about the data that countries do collect and share, he says.

One FAO attempt to measure the lack of adequate food is a five-year pilot exercise to create a new global standard for estimating food insecurity based on people’s experiences rather than estimates of calorie intake. This project, called Voices of the Hungry, collected data from 147 countries last year as part of the Gallup World Poll — including responses to questions such as whether people had to skip a meal or eat only a few kinds of foods because they lacked money or other resources. The first results from the project are due to be published next month.

References

[1] State of food insecurity in the world 2015: In brief (FAO, 27 May 2015)

[2] Thomas Pogge Food and nutrition insecurity: World hunger books are cooked (World Nutrition, July 2015)

Artiklen er oprindeligt bragt på SciDev.Net og gengives her med Creative Commons-licens.