En halv milliard dollars har landbrugssektoren tabt i den brasilianske kyststat Espirito Santo grundet den værste tørke i mindst 80 år. Tørken har allerede ramt vand- og elforsyningen, og nu mærker den vigtige landbrugssektor vandknapheden, der eksempelvis går ud over kaffeproduktionen.

Det fremgår af hjemmesiden for Americas Society/Council of the Americas, der er en amerikansk sammenslutning af forretningsfolk og andre interesserede i latinamerikanske forhold.

Brazil’s southeast region continues to grapple with the ongoing effects of the worst drought in eight decades.

Even though Brazil has the largest freshwater reserves in the world, the country’s largest city is running out of water, and the water shortage is hurting one of the country’s most important industries: agriculture.

Brazil is the world’s third-largest agricultural exporter, and the sector represents nearly 6 percent of the country’s GDP. Irrigation for farming accounts for around 72 percent of water use in Brazil, compared to just 9 percent for urban consumption.

But the drought means less water for producers, leading to crop losses in one of the country’s agricultural centers.

Food Production Affected in São Paulo

In São Paulo state—one of the worst hit areas—agribusiness represents 15 percent of GDP. Some farmers there say they’ve lost almost a third of their crops due to water shortages. The Agricultural Economy Institute estimates that last year may account for the state’s worst agricultural losses in half a century.

For example, on the state’s coffee plantations, many new crops lost their fruit due to the dry weather, and around 20 percent of the state’s citrus crops died. The 2013-2014 bean crop production stood almost 10 percent lower than the previous year, while corn production fell by 26 percent.

Production of soy, one of the country’s largest export crops, shrank 17 percent over the same period. This year, sugarcane farmers are expected to see a nearly 12 percent production decline. Plus, the cost of beef went up 22 percent last month as a result of the drought.

In this state, some farmers are experimenting with different techniques to reduce water used in irrigation. That’s because starting in October, authorities began locking taps used to pump water from streams and rivers to farms.

In February, the governor authorized the police to carry out this task, and to impose fines on those who disobey. Farmers will receive compensation through financial credit from the state in some cases.

Coffee Crops Hit in Southeastern States

São Paulo’s producers aren’t the only ones affected by the drought. Minas Gerais, a major agricultural state, is Brazil’s largest coffee producer. But the drought meant crop production fell across the board, including coffee, rice, soy, and corn. In Uberaba, the state’s largest corn producer, the mayor declared a state of emergency this month.

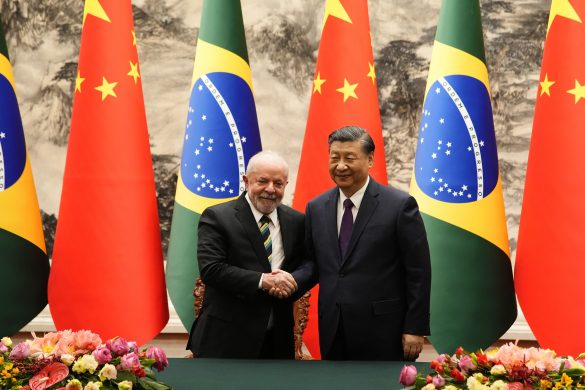

Help may be on the way; after Governor Fernando Pimentel went to Brasilia in January to meet with President Dilma Rousseff, the federal government pledged around $286 million in projects to fight the drought.

In the small coastal state of Espirito Santo, the drought has wrought an estimated half billion dollars* in losses to the agricultural sector. The dry weather hit the coffee industry hardest, resulting in losses of nearly a third of crops and almost $340 million last year. In some municipalities, half of coffee crops were lost.

And while Rio de Janeiro is known for oil and industrial production, its agricultural sector is also feeling the drought’s effects. On January 26, the Rio state government launched a nearly $19 million contingency plan to address the drought’s affects on local agriculture.

In this state, the drought led to agricultural losses of around $35 million in the third quarter of 2014 alone. Around 2,000 cows died during the drought so far. Governor Luiz Fernando Pezão met with Rousseff last month to discuss his drought plan.

What Should the Government Do?

Some experts warn that the drought isn’t just an issue for consumers, and the government must address water use for agriculture. José Graziano da Silva, the Brazilian director-general of the Food and Agriculture Organization, told BBC Brasil that the drought’s impact will be “huge” on all agricultural products, and that higher food prices are likely in the coming months.

He noted a few possible solutions, including creating more food stocks and developing drought-resistant crops. Plus, the drop in food production can harm other industries.

“In the most affected regions, a fall in productivity is nearly certain given a domino effect on supply chains,” a technical advisor at the National Agriculture Confederation told Carta Capital.

Edson Matsura, an agricultural engineering professor at Unicamp, explained to Jornal do Brasil that it’s not just about irrigation, since many grain producers rely on rain. Given the low rainfall, he said the government shouldn’t restrict water use for farmers, who ensure the country’s food production.

However, alarm bells may not be going off in Brasilia just yet. On February 11, Agriculture Minister Kátia Abreu said that the drought is not causing a “deep crisis” in Brazil’s overall agricultural production.

She does not believe food security will be affected, especially since two of the country’s biggest agriculture producers—Mato Grosso and Parana—are not experiencing water shortages.

“The government’s main concern is people [consumers] and industrial production,” she added.