His first son is a senator for the state of Rio do Janeiro. His second son a municipal councillor in the city of Rio, and his third is a federal deputy for the state of São Paulo. And he himself has served seven terms as deputy and as member of several political parties.

Yet Jair Bolsonaro, the favourite candidate for Brazil’s upcoming runoff presidential elections, likes to present himself as a new man who operates outside of the “system”.

The rhetoric of a new man, untainted by the culture of corruption that prevails among the political class, is a powerful device. It’s succeeded in folding the interests of disparate social categories into those of seasoned right wing politicians.

Bolsonaro is candidate for the Social Liberty Party. He’s the author of incendiary pronouncements, happily racist, misogynist and homophobic. The former army captain has managed to coalesce eclectic crowds whose commitment to democracy depends on the exclusion of entire sections of Brazilian society. He has colossal support among Brazil’s prolific evangelical communities. These have re-purposed their religious fervour to passionate hate and the demonising of adversaries.

Bolsonaro assuages the fears of a middle class that feels it’s lost privilege. He also confirms their aversion for Brazil’s internal “others” – namely black Brazilians and various Indian communities. In fact, he promises to keep privilege spaces of university education, residential suburbs and commercial spaces free from poor people.

For Bolsonaro, the choice Brazilians have to make is rather simple: it’s either “prosperity, freedom, family and God” – in other words him, or “the path of Venezuela”. In other words Fernando Haddad’s Workers’ Party.

In the first round of elections, Bolsonaro’s party secured 46% of the total vote. Haddad’s Workers’ party secured 29%. Haddad is routinely the victim of his opponent’s foul mouth. Bolsonaro is a slavery-denialist, who claims that the Portuguese never set foot in Africa and that Africans themselves “delivered” slaves to Brazil.

Needless to say his views on Africa are narrowly informed by the prism of Brazil’s uneasy, strained and unresolved racial question. As a result, his government can be expected to scale back Brazil’s engagements with the continent.

The end of Lula’s Africa moment?

Bolsonaro is expected to turn threats by the current administration to close Brazilian embassies in Africa into policies. Cutbacks on scholarships for African students are also expected.

At home he’s expected to put further restrictions on immigration and to withdraw into national priorities. These include Brazil’s economic doldrums, its fractured society, the high levels of crimes and more crucially the economic recession.

The only area where a Bolsonaro government policy might intersect with previous policy could be the military cooperation and the trade in military equipment.

If little is known about Bolsonaro’s views on foreign policy in relation to Africa, his running mate, General Hamilton Mourão, has been very clear. During a recent speech he criticised Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff’s South-South diplomacy claiming that it had resulted in costly association with “dirtbag scum” countries (African) that did not yield any “returns.

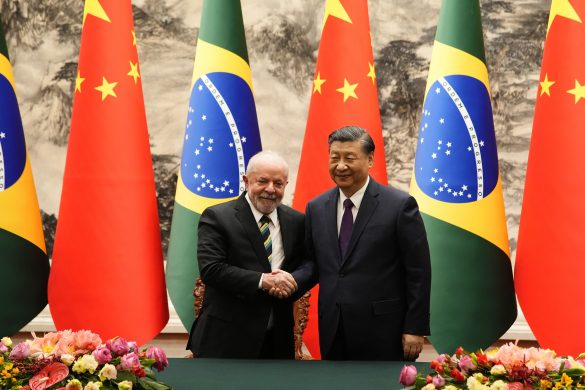

Africa was the centrepiece of Lula da Silva’s geopolitical aspirations for Brazilian status in an expanded and reformed multilateralism. In eight years of his presidency he visited 27 African countries over 12 trips.

But Brazil’s Africa moment had already began to fade under Rousseff. The election of Bolsonaro is likely to signal the beginning of the end of Africa-Brazil relations as we know them. It could even mean the end of the five country grouping known as BRICS as he has promised to review Brazil’s participation in the coalition.

Brazil’s relations with Africa have been particularly strong with the Lusophone countries of Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, and Sao Tome and Principe. Angola in particular became a springboard in Brazil’s expansion into the South Atlantic beyond the Lusophone world.

Lula da Silva sought to institutionalise the new Global South framework in the form of a biannual Africa South America Summit and also through the India, Brazil South Africa Dialogue Forum. He doubled Brazil’s diplomatic presence in Africa between 2000 and 2010. By 2010 there were 39 embassies. Over the same period, 18 African embassies opened in Brasilia.

These various initiatives fed a momentum in Brazil’s rise to global prominence. Brazil was for instance able to get José Graziano da Silva elected Director-General of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation with the strong support of African countries.

Beyond punctual strategies, Brazil’s engagement with Africa served to enhance its global standing and to buttress Brazil’s ambition to become a leading voice of the Global South.

Economic strategies

Brazil’s economic strategies took an expansionist pattern similar to that of other emerging powers. They targeted resources-rich and fast growing economies. Main export destinations were Egypt and Nigeria. Imports come mainly from Algeria and Nigeria.

Between 2000 and 2013, trade between Brazil and Africa expanded from $USD4.3 to USD$28.5 billion. But it dropped by USD$12.4 billion in 2016 following economic recession and political upheaval in Brazil.

Brazil’s economic engagement with Africa is not without its problems. For instance, the infrastructure giant Odebrecht is at the heart of Operação Lava-Jato (Operation Car War) which exposed the largest corruption scandal in the history of modern democracy. It involved over 200 leaders across the political and business sectors and over USD$2 billion.

Under Bolsonaro, economic ties can be expected to take a different turn. Institutions such as the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation can be expected to grow in prominence in Africa as he makes a big push for agro-business expansion. This will come with its own set of problems, notably pollution caused by fertilisers and attendant health risks. That, however, is unlikely to deter him.

—

Denne artikel er oprindeligt bragt af The Conversation. Læs den originale udgave her.

Amy Niang er lektor i Internationale forhold ved University of Witwatersrand i Sydafrika. Niang er pt. gæstelektor ved University of Sao Paulo i Brasilien.