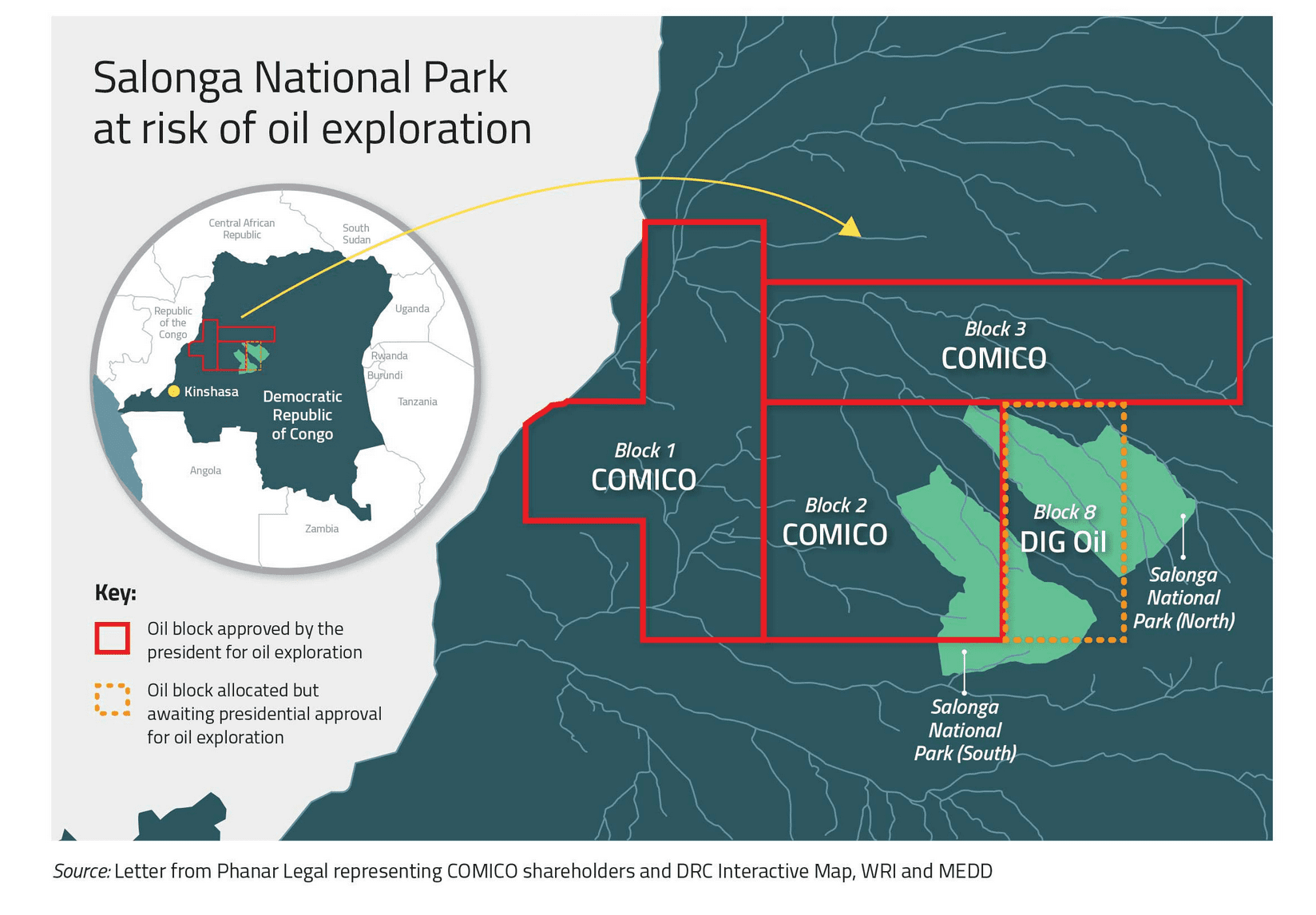

(Global Witness) As we have previously revealed, the Democratic Republic of Congo government is attempting to reclassify swathes of two UNESCO protected World Heritage Sites – Salonga and Virunga National Parks – to allow oil exploration to take place. In our new investigation, we shine a light on the opaque ownership and secret deals of one company that potentially stands to gain from government attempts to open up the area to oil, COMICO, which was allocated an oil block that partially overlaps Salonga National Park.

We expose how individuals involved in the original deal to purchase these controversial oil rights include a politically connected individual, a convicted fraudster, a businessman embroiled in the Brazilian ‘Car Wash’ scandal and mysterious shell companies.

Moreover, the details of the contract remain unknown, in contravention of Congo’s own oil law. The opacity surrounding both the company and the terms of the deal raises serious concerns.

The prospect of oil work represents an urgent threat to Salonga’s important and fragile ecosystem, while the lack of transparency is especially concerning as the country remains embroiled in a political crisis.

World’s second largest tropical rainforest under threat

One of the three oil blocks assigned by the government to COMICO, a part UK-owned company, encroaches on Salonga National Park, the world’s second largest tropical rainforest and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984. The park is home to up to 40 percent of the world’s Bonobo population and many other endangered and rare species such as forest elephants, Congo peacocks, hippopotamuses and giant pangolins.

At the heart of the Congo basin, Salonga National Park stretches over 36,000 square kilometres – an area larger than Belgium. Its size means it plays a fundamental role in climate change mitigation and carbon storage.

UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee is clear that any form of mineral, oil and gas exploration or exploitation is incompatible with World Heritage status. If even World Heritage status cannot protect fragile ecosystems from oil work, it sends a message that the entire planet is up for sale to the fossil fuels industry, with potentially devastating environmental consequences.

A deal shrouded in secrecy

As well as the huge environmental risks associated with the deal, it is alarming that we don’t know in full who is behind COMICO or the terms of the deal.

At its formation in 2006 COMICO was controlled by two men: Montfort Konzi, a former Congolese politician and businessman, who was a cabinet member of Jean-Pierre Bemba’s Congolese political party Mouvement de Libération du Congo; and Idalécio de Oliveira, a controversial Portuguese businessman linked to the Brazilian Car Wash scandal.

Various companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions appeared to have obtained shares in COMICO just as it was in the process of acquiring Congolese oil permits. We have been able to trace links between two of these companies and Norman Leighton, a former business associate of Oliveira who was previously convicted of playing a part in a fraudulent investment scheme.

Despite our best efforts, we were unable to trace the ownership of one of these offshore companies – Shumba International, which held a 1.5 percent share of COMICO as of 2007. Shumba is now listed as ‘defunct’ on the Mauritius company register.

The adjustment of COMICO’s structure in this way, involving opaque offshore companies picking up shares just as COMICO was in the process of obtaining its contract, raises serious red flags, as does the presence of a former Congolese politician, Konzi, in the historic ownership structure.

Without full disclosure of the owners of these offshore companies we cannot be sure who benefits or has benefitted from this company that now owns controversial oil exploration rights in Salonga National Park. When contacted by Global Witness, lawyers representing the COMICO shareholders we have been able to identify, said the confidentiality around the full ownership of COMICO was for “legitimate commercial reasons unconnected with bribery and corruption or other financial crime”, and they stated “none of the other beneficial owners have been convicted of bribery, corruption, fraud or other financial crime.”

The opacity around COMICO’s ownership is matched by the lack of transparency surrounding the contract.

COMICO’s production sharing agreements (PSAs, i.e. its contract) were initially signed over 10 years ago, but the company was not able to begin exploration until Congo’s President Joseph Kabila signed an ordinance in February this year.

Congo’s oil law, passed in 2015, stipulates that new contracts should be published within sixty days of being approved. However, sixty days after President Kabila gave presidential approval authorising COMICO’s contract, there was – and, as of 28 May 2018, still is – no sign of the contract

Lawyers for COMICO told Global Witness that a $3 million signature bonus had been made in 2007, but that “no other payment, direct or indirect, have [sic] been made to the Congolese government or its officials or its representatives.” However, as the contract has not been made public, it is impossible to assess the terms of this oil deal, to understand whether it is beneficial for the people of Congo, or to know whether potentially significant payments into government coffers, such as signature bonuses (upfront payments made by companies to governments upon the completion of a contract), have been paid.

Need for transparency more urgent than ever

There is a long history of companies and political elites swooping in at times of crisis to exploit Congo’s natural resources behind closed doors, to the detriment of its people and natural habitats. Now, more than ever, the need for transparency in Congo’s natural resource deals is key.

The Congo still ranks among the poorest countries in the world and is 176th out of 187 on the most recent Human Development Index calculated by the UN. It had the highest number of internally displaced people in Africa last year, with almost 2.2 million people forced from their homes. Furthermore, the country is currently in the midst of an Ebola outbreak and the risk of famine and conflict is looming large.

In such a dire context, and with the Congolese economy depending almost entirely on its natural resource sectors for export revenues, it is vitally important that deals in these sectors are conducted transparently and that the revenues are used for the benefit of Congo’s people.

Moreover, the political climate in Congo is currently very tense as presidential elections due to be held in November 2016 have been repeatedly delayed, sparking widespread protest. Conflicts have been re-erupting across the country and appearing even in a region that had historically been peaceful. President Kabila has overstayed his constitutionally allowed two terms in power and has not ruled out changing the constitution to remove term limits so that he could stand for election a third time.

Congo’s political crisis is likely to worsen as it approaches the new December 2018 deadline for elections. In this atmosphere, opening up Salonga National Park to oil raises the possibility that the Kabila regime is seeking to extract more revenue from the country’s natural resources during this precarious time – possibly to build up a financial war chest for elections.