Om skribenten

Sibylle Riedmiller spent most of her professional life in Latin America and Africa, working with education reform and natural resource management projects with UNESCO, GTZ/GIZ and others. Worked 1998 for Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke in a review-team in Tanzania.

From 1991, she developed award-winning Chumbe Island Coral Park in Zanzibar, a privately managed marine park and forest reserve that is now fully funded with income from ecotourism. A passionate sailor and diver, Sibylle lives in Tanga/Tanzania since 1982, where she is now semi-retired.

Ilkurot Village is on the arid side of the slopes of Mount Meru (Nordtanzania), so most visitors remember it as a very dry, dusty and windy place.

But not only nature is seen to be harsh there, Ilkurot has also been known as a ‘bad’ example of Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke’s partnership,

Because here ‘poor’ leadership, a predominance of ‘traditionalist’ attitudes among its people and a general reluctance to work in groups (as required by Government extension officers and donor organisations alike) seem to frustrate any effort of promoting ‘development’.

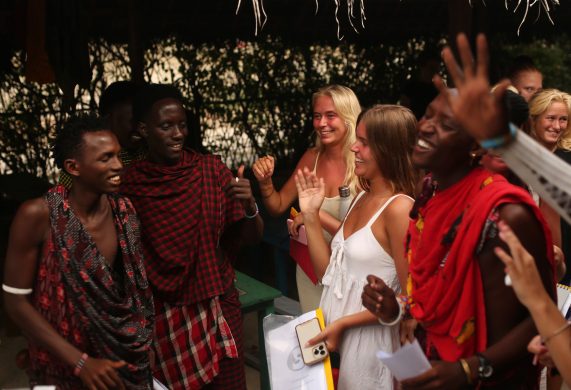

Most people are Waarusha, closely related to the Maasai in their culture and love for cattle, but they are not nomads and have a long tradition of farming.

Mødet med Ndungoti

I meet Ndungoti on her way back from the waterplace shared by women washing clothes and herds of cattle. She seems to be in no hurry but rather curious about that Mzungu (hvide europæer), so a chat develops and leads to an invitation to her house.

We approach a large and beautifully decorated round hut: several strips of meandering dotted lines circle the great walls, incorporate shining pieces of mirror, silvery paper wrappings of sweets, bottoms of beer cans and blue plastic tops of margarine containers.

The dark inside has a spacious centre (where a three-stone fireplace faces the door) and three distinct compartments separated by round poles stuck into the ground: one is the sleeping place for the family, the other two are used at night for goats and up to three cows.

The functionality and beauty of every detail and general cleanliness make me understand that these are people very proud of their own culture and traditional skills, rather than ‘too poor to afford a modern house’.

Har ikke set manden i årevis

We are greeted by Ndungoti’s three year old son and her old father in law. Her husband is working in Nairobi, I am told, and has not come home for the last two and a half years.

She is longing for him to visit her to have more children, but he is only occasionally sending her some cooking oil and soap and very little money through relatives and friends.

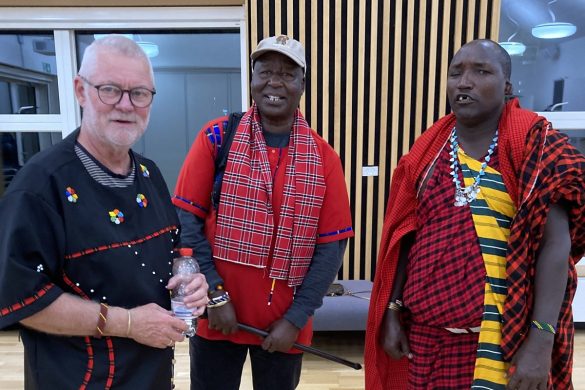

After a while more women and children from the neighbourhood have gathered in the house, dressed in colourful cloth and strings of beads dangling from their extended earlobes and wound around their necks, arms and ankles.

I am now surrounded by curious people who seem to relish the opportunity to have an Mzungu at such close range.

Constantly somebody is touching my hair, the skin on my forearm, pulling my socks and the sleeves of my T-shirt and peeping into my bag with the note book, while I try to concentrate on my chat with Ndugoti and the few other women who know some Swahili.

Europæiske spørgsmål og afrikansk virkelighed

Are they members of the women groups for vegetable farming and chicken keeping organised by the MS-DWs (u-landsfrivillige) in the village, and how is it going?

Yes, Ngudoti and a few others have joined in, but they go there only occasionally, every woman has enough work with her own shamba and garden, and then the chairwoman is not always informing everybody about a meeting or when visitors are coming.

Her neighbour, Nabulu, has got a baby and has to stay indoors for nine months, as the custom requires, so she dropped out, while others just don’t see the point why they should do in a group what they can better do on their own at home, with the help of their children and family members.

What are the advantages of the groups? I ask. Well, if you organise, you may be able to get something in return, I am told. There seems to be no other good reason.

But is there no training in the groups? Yes, this is something: Ndugoti brings an exercise book where the first five pages are filled with lessons on chicken keeping, the last is one year old.

Kyllingerne i bogen og på marken

Photocopies of sketches on how to construct an improved chicken shed and on how to transplant tree seedlings are glued in between.

What do these drawings mean? I ask her. She explains that they show a hand holding a tree seedling over something that she cannot identify (it is the schematic diagram of the plant hole), and the drawing of a tree nursery that she believes is showing a chicken shed.

And what about the content of the lessons? She has some chicken freely roaming about the compound for food, maybe there is something she can improve on that?

Together we go through a neatly copied hand-written text on ‘How to prepare an improved chicken feed’: you mix 40 kg of maize flour with 20 kg of sorghum flour, 10 kg of fish meal and other ingredients … !!!???

These amounts would be enough for large scale chicken farms with at least several hundreds of birds, and the same stuff would feed a family for a whole month.

Når man ikke kan læse og skrive

Ndugoti is surprised by my reaction: it turns out that she does not know how much a kilogram is anyway, also many of the ingredients are not available or very expensive and she has not yet received those ‘modern’ chickens, so the whole lesson was more an exercise in handwriting.

And this was actually what she wanted to show me: that she is literate, while the other women around us are not, nor do any kids in the room go to school.

Why not? I ask. Shrugging of shoulders around me, no comments, I realise this is not a topic they are interested to discuss, maybe because it is too sensitive and loaded with reproaches that ‘parents do not appreciate the importance of education’.

Maybe nobody has ever bothered to understand their reasons for keeping out of a school system which not only ignores but even despises their culture and needs.

For the Waarusha, children are part of the family economy from an early age. Once they go to school they are lost and will not anymore learn from their parents what is needed for the survival of their culture and their way of life.

Er sult er stort problem lige her?

Another question: Is hunger a big problem here?

This has been an unusually rainy year but the area is known to be seasonally threatened by famine when shambas and pastures are turned into dustbowls by the scorching sun and winds during the dry season.

I therefore remember to ask what every outsider, government agent or donor representative, seems to be interested in: What are your problems?

The women look puzzled. Yes, somebody has promised a maize mill (the nearest one is a bit far to walk), and the councillor has given a ‘building machine’ (a cinva ram to make building blocks) to some young men downhill.

Is there anything I can offer? I am asked. No, there is nothing I have to offer, nor should anybody else offer a ready-made package of ‘solutions’, when there is no perceived problem, or without asking for their own solutions, which may then take quite some time to develop … Nothing pressing comes to their minds. OK, no big problem, really.

Føler sig ikke fattige – tværtimod

It is getting late, I am leaving a group of gentle, seemingly content people, proud of their culture, openly talking about their lives when in their own home ground and very inquisitive about how things are in that strange world I am coming from.

Are they ‘poor’? During these hours we shared chatting, these women certainly did not consider themselves ‘poor’, nor me, the Mzungu visitor, ‘rich’.

Maybe ‘poor’ is a role people learn to adopt when dealing with outsiders who unconsciously insist to see them that way, so they have a justification to ‘help’ them – a defence mechanism against paternalistic domination from outside by a people who want development on their own terms, but do not know yet, how this could work out …

Bearbejdet uddrag fra: MS-Tanzania Country Programme Review, MS, København 1998.

Kom og vær med som skribent!

Skriv et indlæg til denne spændende serie. Det har mange fortællelystne personer allerede gjort, og deres indlæg er offentliggjort løbende, siden serien indledtes 13. juli.

Det kan være episoder eller dramatiske hændelser, du har oplevet “derude”, og som er værd at bringe videre.

Peter Sigsgaard vil meget gerne kontaktes på e-mailadressen [email protected] eller telefon 45 82 12 39

Indlæg er honorarfrie.