8. april 2015 [Oakland] – Internal Chevron videos of secret “pre-inspections” of well sites during the Ecuador pollution trial show company technicians finding and then mocking the extensive oil contamination in areas of the Amazon rainforest that the oil giant had claimed in various courts had been remediated, said the environmental and human rights advocacy group Amazon Watch.

Whistleblower

An apparent Chevron whistleblower sent dozens of internal company videos to Amazon Watch with a note signed “A Friend from Chevron.”

Most of the videos – some of which can be seen on the Amazon Watch website – show Chevron employees and consultants secretly visiting the company’s former well sites in Ecuador to find “clean” spots where they could take soil and water samples at later site inspections when the presiding trial judge would be in attendance.

“This is smoking gun evidence of Chevron’s corruption caught on tape,” said Kevin Koenig, Ecuador Program Director at Amazon Watch who has worked with the affected indigenous and farmer communities for two decades.

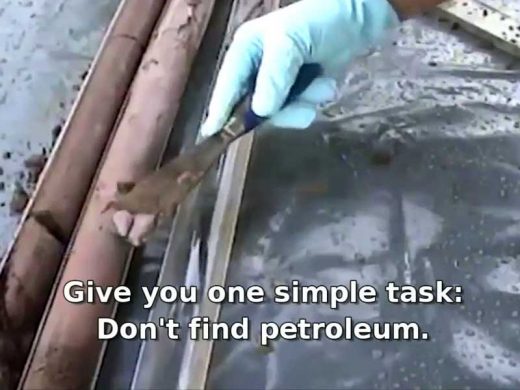

In the videos, Chevron employees and consultants can be heard joking about clearly visible pollution in soil samples being pulled out of the ground from waste pits that Chevron testified before both U.S. and Ecuadorian courts had been remediated in the mid-1990s. (Chevron bought Texaco in 2001 and is now liable for the company’s environmental problems.)

In a March 2005 video, a Chevron employee, named Rene, taunts a company consultant, named Dave, at well site Shushufindi 21:

“… you keep finding oil in places where it shouldn’t have been…. Nice job, Dave. Give you one simple task: Don’t find petroleum.”

Langvarig retssag

After reviewing 105 technical evidentiary reports documenting extensive pollution, eight appellate judges, including Ecuador’s Supreme Court, affirmed Chevron’s liability in 2013 after 11 years of legal proceedings in the company’s chosen forum.

Damages were set at $9.5 billion, but Chevron thus far has refused to pay.

Chevron Chairman of the Board and CEO John Watson promised the Ecuadorians a lifetime of litigation, saying the 22-year-old legal battle will end when “the plaintiffs’ lawyers give up.”

Amazon Watch has criticized Watson’s strategy to escape accountability for the contamination and vilify Chevron’s critics.

Texaco and Chevron testified Shushufindi’s pits had been cleaned but when Chevron’s technicians find oil, Rene snickers about the contamination with several consultants:

Dave said to Rene: Good news! Petroleum!

Rene: No! No, check it again… Ok it is, it is, it is. Well, we might as well stop them now, shh stop them, just yeah, we’re done. We’re trying to draw a clean core and obviously we didn’t go out far enough.

Dave: Yeah, but was there supposed to be anything this far south?

Rene: No, now we’ve got a headache.

Later, Rene jokes about blaming the consultants for finding contamination where it shouldn’t have been: “Shoot the messenger. …and then it’s your fault, not our fault for putting it there, see? It’s a brilliantly conceived strategy.”

Rene refers to “Dave” in the video as an employee of URS, a San Francisco-based engineering company used by Chevron in the Ecuador trial.

Konsekvenser for de lokale beboere

A Chevron cameraman also conducted revealing interviews with area residents during and after the pre-inspections, which took place in 2005 and 2006.

The Chevron videos also show local villagers complaining about the pollution, often blaming Texaco (now owned by Chevron) and recounting how the American oil company never cleaned some of the waste pits and instead covered them with dirt to try to hide the contamination.

For example, a Chevron cameraman asked questions of a resident named Merla who has lived in the area for over 30 years near well site Shushufindi 25, where Texaco and Chevron said pits had been cleaned.

Merla: We’ve had our cows die… They drank the water where the oil had spilled. Back then, that whole area was full of crude oil. The water there was filthy. They came and stopped the leak and they just left all of the crude oil there. It’s pure crude there. In the middle, it’s a thick ooze and you’d sink right down into it.

Chevron Interviewer: When was this oil spill?

Merla: More than 20 years ago… But I still remember it, how there was oil over everything. The cows still die there. They came, threw some dirt on top of the crude oil, and there it stayed.

Chevron Interviewer: How long ago did they cover up the pit?

Merla: 19 years… Texaco. They came here and just covered up the oil. They kept saying they were going to clean it up and they never did. And then they disappeared.

Chevron Interviewer: Did they remove the crude oil?

Merla: They dumped a lot of dirt on it and that was it.

Additional videos are being reviewed by Amazon Watch and will be released in the coming weeks.

Hemmeligholdte videoer

Chevron never turned over any of the secret videos to the Ecuador court conducting the trial.

Nor did the company submit its pre-inspection sampling results to the court, despite the fact evidence later emerged that they confirmed high levels of cancer-causing oil contamination at many of the company’s former well sites in the country.

In a related but separate arbitration matter, a tribunal recently ordered the company to turn over contamination test results from the pre-inspections, reflected in this document.

It shows Chevron found illegal levels of contaminants at 76 former company well sites in Ecuador during both the pre-inspections and the official judicial inspections, confirming yet again the finding of liability against the oil major in its chosen forum of Ecuador.

Amazon Watch received dozens of DVDs from the whistleblower by mail at its Washington, DC office.

All were titled “pre-inspection” with dates and places of the former oil production sites where Chevron sought to plan its sampling strategy to mislead the Ecuadorian court during the judicially-supervised site inspections.

Inside the package was a handwritten note stating: “I hope this is useful for you in your trial against Texaco/Chevron. [signed] A Friend from Chevron.”

Leaders of Amazon Watch said they were flabbergasted to see the contents of the videos.

Korruption fanget på video

“These explosive videos confirm what the Ecuadorian Supreme Court has found after reviewing the evidence: that Chevron has lied for years about its pollution problem in Ecuador,” said Kevin Koenig.

“The videos show company technicians discussing in stark terms the presence of oil pollution in places where they told the court it didn’t exist. This is corruption caught on tape.”

“This is smoking gun evidence that shows Chevron hands are dirty – first for contaminating the region, and then for manipulating and hiding critical evidence,” said Paul Paz y Miño, Director of Outreach at Amazon Watch.

“While its technicians were engaging in fraud in the field, Chevron’s management team was launching a campaign to demonize the Ecuadorians and their lawyers as a way to distract attention from the company’s reckless misconduct.”

“The behavior of Chevron throughout the litigation reflects a grossly unethical internal culture that clearly is encouraged at the highest levels of the company,” Paz y Miño added.

On April 20, a federal appellate court in Manhattan will hear oral argument in the appeal of fraud charges brought by Chevron in a U.S. court as part of the company’s retaliation strategy to evade paying the Ecuador judgment.

In 2011, a federal appeals panel ruled against Chevron when the company obtained an unprecedented ruling purporting to block enforcement of the Ecuador judgment anywhere in the world.

This time, Chevron is seeking to block collection of the judgment anywhere in the world via an order that the villagers argue violates domestic and international law and has no precedent.

Ufine metoder

The videos also are consistent with prior examples of Chevron’s efforts to corrupt the evidence-gathering process during the Ecuador trial.

In 2009, Chevron consultant Diego Borja admitted he switched out dirty samples for clean ones during the Ecuador trial.

In 2011, a U.S. court forced Chevron to release its “judicial inspection playbook” that directed company technicians to only lift soil samples from clean spots usually up-gradient from the company’s toxic waste pits.

Clean samples and dirty samples were sent to different labs, with the plan being that only the cleanest samples would be submitted to the court.

Despite this trickery, the scientific evidence showed that the soil samples were so saturated with oil that even Chevron’s own technical reports submitted to the court still demonstrated illegal levels of contamination, according to court findings.