Beirut (HRW): Authorities at a maximum security prison in Cairo that holds many political prisoners routinely abuse inmates in ways that may have contributed to some of their deaths.

Staff at Scorpion Prison beat inmates severely, isolate them in cramped “discipline” cells, cut off access to families and lawyers, and interfere with medical treatment, according to the 80-page report, “‘We Are in Tombs’: Abuses in Egypt’s Scorpion Prison.” The report documents cruel and inhuman treatment by officers of Egypt’s Interior Ministry that probably amounts to torture in some cases and violates basic international norms for the treatment of prisoners.

The abuse in Scorpion, where inmates are held in cells without beds or items for basic hygiene, has persisted with almost no oversight from prosecutors and other watchdogs, behind a wall of secrecy kept in place by the Interior Ministry.

“Scorpion Prison sits at the end of the state’s repressive pipeline, ensuring that political opponents are left with no voice and no hope,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Its purpose seems to be little more than a place to throw government critics and forget them.”

Conditions deteriorated under Sisi

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 relatives of inmates held in Scorpion, two lawyers, and one former prisoner, and reviewed medical files and photos of sick and deceased prisoners.

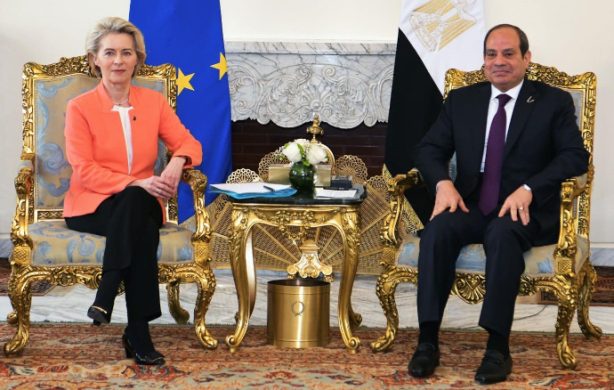

Since July 2013, when Egypt’s military, led by then-Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, overthrew Mohamed Morsy, the country’s first freely elected leader and a high-ranking Muslim Brotherhood member, the Egyptian authorities have engaged in one of the widest arrest campaigns in the country’s modern history, targeting a broad spectrum of political opponents.

Relatives said that conditions in Scorpion deteriorated drastically in March 2015, when al-Sisi, who was elected president in 2014, appointed Magdy Abd al-Ghaffar as interior minister. Between March and August 2015, Interior Ministry officials banned all visits by families and lawyers, essentially cutting off the prison from the outside world.

The ban prevented families from delivering much-needed food and medicine otherwise unavailable in the prison – where there is no hospital or regular visits from a doctor – and amounted to what relatives described as a “starvation” policy that left inmates sick and gaunt.

Between May and October 2015, at least six Scorpion inmates died in custody. Three of their families agreed to speak with Human Rights Watch. Two of the men had been diagnosed with cancer and one with diabetes. Their relatives said that the authorities prevented the men from receiving timely treatment or medicine deliveries, refused to consider conditionally releasing them on medical grounds, and failed to investigate their deaths.