A Lebanese journalist was convicted in absentia of defaming acting Minister of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants Gebran Bassil in a Facebook post.

A court in the western Lebanese city of Baabda sentenced Fidaa Itani to four months in prison and a fine of 10 million Lebanese lira (roughly USD $6660) on June 29, 2018.

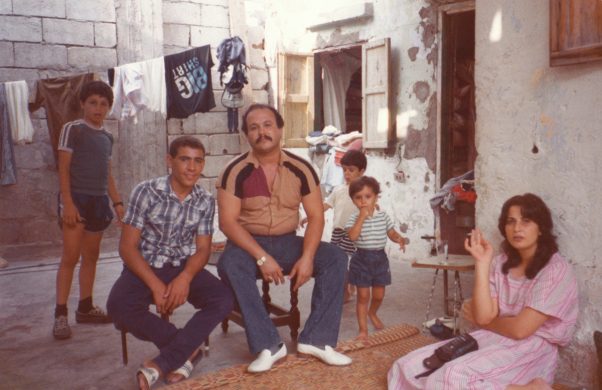

Fidaa Itani is a journalist who focuses on Syria and the refugee crisis.

The Facebook post in question leveraged a complex critique of political and military actions by various powerful actors in Lebanon. Itani decried raids carried out by the Lebanese army in Arsal last year, which resulted in the death of Syrian citizens in detention. He also criticized the continuous nationalist push for the forced removal of refugees on Lebanese territories.

Itani went on to express concern about the Lebanese political party and militant group Hezbollah. Itani has publicly opposed Hezbollah’s military intervention in Syriaon behalf of the Assad regime.

Shortly thereafter, lawyers for the army and the presidency filed a lawsuit against Itani. On top of this, he began receiving direct threats from people associated with Hezbollah. In short order, he fled the country and sought exile in the UK.

In an interview with the francophone Lebanese newspaper L’Orient le Jour, Itani explained that the original suit, filed by lawyers claiming to represent the Lebanese president and the army, seems to have vanished and now been replaced by the case brought by Gebran Bassil.

I don’t know how the first legal action disappeared, nor what was cooked with the case between services of the military intelligence and the president of the republic, or even Hezbollah. Although it seems that Gebran Bassil volunteered to institute an action in their stead.

Itani also said that he had not received official confirmation of the sentence, and only heard the news from media reports. He also told Maharat Foundation, a free speech NGO, that acting Minister Bassil has filed a total of nine cases against him, including this one.

Reacting on both Facebook and Twitter, Fidaa Itani was unsurprisingly critical of the judge’s decision. Sharing an article citing his prison sentence, he commented: “More repression and more robberies.”

The sentence of Itani was reported, criticized and denounced by some Lebanese and international organizations.

In an email sent to reporters, Bassam Khawaja, Lebanon researcher at Human Rights Watch, said:

Sentencing a journalist to four months in prison for a critical Facebook post is an outrageous attack on free speech that lays bare the lack of meaningful protections for freedom of expression in Lebanon. Lebanon’s new parliament should act quickly to abolish laws that criminalize defamation, which are disproportionate, unnecessary, and violate international human rights law.

Indeed, Lebanon’s penal code criminalizes defamation and makes special provisions against insulting the president, the flag, and other public officials. The country’s military code criminalizes “insulting the flag or army”. These offenses all are punishable with fines and prison time, and offer no special exception for journalistic work.

According to Freedom House 2016 Report on Lebanon:

Lebanese journalists complain that media laws are chaotic, contradictory, and ambiguously worded. Provisions concerning the media, which justify the prosecution of journalists, can be found in the penal code, the Publications Law, the 1994 Audiovisual Media Law, and the military justice code.

Ytringsfriheden under pres i Libanon

In Lebanon’s legal landscape, court cases against journalists are not a new phenomenon, but such incidents have multiplied in recent months, with a smattering of charges against journalists, TV show hosts, and commentators.

On January 24, 2018, TV comedy show host Hisham Haddad was prosecuted for making jokes at the expense of Prime Minister Saad Hariri and Saudi crown prince Mohammad Bin Salman.

In March 2018, the owner of the website Lebanon Debate was sentenced to six months in prison and was ordered to pay 10 million Lebanese Lira, after being found guilty of libel in a case brought by the Director General of Customs.

In November 2017, prominent Lebanese TV host Marcel Ghanem was prosecuted for obstruction of justice after he resisted charges brought against two of his guests, both Saudi journalists, who denounced Lebanese President Aoun and Minister Bassil of being “Hezbollah’s partner in terrorism.” The case against Ghanem was dropped.

In another article written by L’Orient Le Jour, Marcel Ghanem was reported saying that the arrests of journalists and their convictions was the result of “muzzling practiced by the ruling powers under the cover of the struggle against terrorism or Israel”.

But public prosecutors are not the only legal entities bringing charges of defamation and libel against media workers. On January 10, 2018, the Lebanon’s notoriously harsh military court sentenced in absentia Lebanese journalist and researcher Hanin Ghaddar for defaming the Lebanese army at a conference held in the USA in 2014. Her sentence was later overturned.

Ten days later, military intelligence summoned human rights defender Ovada Yousef over Facebook posts. Yousef told Human Rights Watch that he was detained by the military and police for four days.

Maharat Foundation, a media and free speech NGO, has called for Lebanese judicial authorities to take into account the right of criticism against public persons:

Maharat also calls on the new parliament to speed up the reforms it has introduced with the MP Ghassan Mukhaiber, notably the abolition of the prison sentence and the preventive detention of anyone expressing his opinion by any means, including the Internet, and broadening the concept of public criticism.

Time will tell if their initiative amounts to real change in the country’s free speech environment.