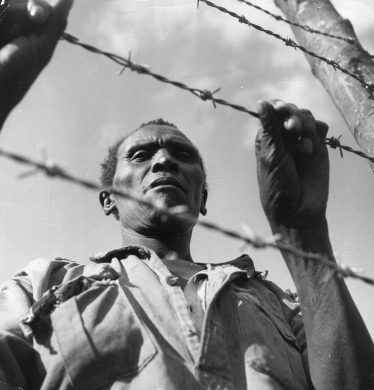

I en udtalelse fra Verdenssundhedsorganisationen, WHO, kommer organisationens topledere sine kritikere i møde og indrømmer, at deres organisation begik en række fejl i forbindelse med bekæmpelsen af verdens hidtil største og mest alvorlig udbrud af sygdommen ebola.

Sygdommen hærgede landene Guinea, Liberia og Sierra Leone i 2014 og ind i 2015 og er fortsat ikke slået helt ned. Udbruddet har koster over 10.000 mennesker livet.

I udtalelsen beskriver WHO’s ledere bl.a., at organisationen manglede kapacitet til at rykke ud til en katastrofe af denne størrelse og ikke magtede at engagere lokalsamfundene og lokale ledere i indsatsen mod sygdommen.

Organisationen har også lært, skriver lederne, vigtigheden af at koordinere indsatsen med andre aktører, så de forskellige organisationer og institutioner ikke træder hinanden over tæerne men i stedet udnytter hinandens styrker.

De oplister herefter en række tiltag, som skal styrke WHO til at imødegå lignende kriser.

Læs hele udtalelsen herunder.

The Ebola outbreak that started in December 2013 became a public health, humanitarian and socioeconomic crisis with a devastating impact on families, communities and affected countries. It also served as a reminder that the world, including WHO, is ill-prepared for a large and sustained disease outbreak.

We, the Director-General, Deputy Director-General, and Regional Directors of WHO, are making this commitment of collective leadership to Member States and their peoples in line with recommendations made by the Special Session of the Executive Board on Ebola held in January 2015. We have taken note of the constructive criticisms of WHO’s performance and the lessons learned to ensure that WHO plays its rightful place in disease outbreaks, humanitarian emergencies and in global health security.

What have we learned?

We have learned that new diseases and old diseases in new contexts must be treated with humility and an ability to respond quickly to surprises. Greater surge capacity contributes to a flexible response.

We have learned lessons of fragility. We have seen that health gains – fewer child deaths, malaria coming under control, more women surviving child birth – are all too easily reversed, when built on fragile health systems, which are quickly overwhelmed and collapse in the face of an outbreak of this nature.

We have learned the importance of capacity. We can mount a highly effective response to small and medium-sized outbreaks, but when faced with an emergency of this scale, our current capacities and systems – national and international – simply have not coped.

We have learned lessons of community and culture. A significant obstacle to an effective response has been the inadequate engagement with affected communities and families. This is not simply about getting the right messages across; we must learn to listen if we want to be heard. We have learned the importance of respect for culture in promoting safe and respectful funeral and burial practices. Empowering communities must be an action, not a cliché.

We have learned lessons of solidarity. In a disease outbreak, all are at risk. We have learned that the global surveillance and response system is only as strong as its weakest links, and in an increasingly globalized world, a disease threat in one country is a threat to us all. Shared vulnerability means shared responsibility and therefore requires sharing of resources, and sharing of information.

We have learned the challenges of coordination. We have learnt to recognise the strengths of others, and the need to work in partnership when we do not have the capacity ourselves.

We have been reminded that market-based systems do not deliver on commodities for neglected diseases – endemic nor epidemic. Incentives are needed to encourage the development of new medical products for diseases that disproportionately affect the poor. The scientific community, the pharmaceutical industry, and regulators have come together in a collaborative effort to vastly compress the time needed to develop and approve Ebola vaccines, medicines, and rapid diagnostic tests. In future, this ad hoc emergency effort needs to be replaced by more routine procedures that are part of preparedness.

Finally, we have learned the importance of communication – of communicating risks early, of communicating more clearly what is needed, and of involving communities and their leaders in the messaging.

What must we do?

We will engage with national authorities and request them to keep outbreak prevention, preparedness and response management at the top of national and global agendas.

We will develop the capacity to respond rapidly and effectively to disease outbreaks and humanitarian emergencies. This will require a directing and coordinating mechanism to bring together the world’s resources to mount a rapid and effective response. We commit to expanding our core staff working on diseases with outbreak potential and health emergencies so we will have skilled staff always available at the three levels of WHO. We will also create surge capacity of teams of trained and certified staff so that we have a reserve force in the event of an emergency.

We will create a Global Health Emergency Workforce – combining the expertise of public health scientists, the clinical skills of doctors, nurses and other health workers, the management skills of logisticians and project managers, and the skills of social scientists, communication experts and community workers. This Global Health Emergency Workforce will be made up of teams of trained and certified responders who can be available immediately. A key principle must be to build capacity in countries, with training and simulation exercises.

We will establish a Contingency Fund to enable WHO to respond more rapidly to disease outbreaks. We must ensure adequate resources – domestic and international – are available before the next outbreak.

We recognize that emergency situations demand a command and control approach and we commit to seamless collaboration between headquarters, regional offices, and country offices. Better WHO systems for rapid staff deployments, data collection and reporting, expansion of laboratory services, logistics, and coordination were developed as the outbreak evolved. These systems will be institutionalized.

The massive international response revealed the unique strengths of multiple partners, including UN agencies. We will build on these partnerships, concentrating on capacities that are most critically needed under the demanding conditions of emergencies.

We will strengthen the International Health Regulations – the international framework for preparedness, surveillance and response for disease outbreaks and other health threats. We commit to strengthening our capacity to assess, plan and implement preparedness and surveillance measures. We will scale up our support to countries to develop the minimum core capacities to implement the IHR. We will establish mechanisms for independent verification of national capacity to detect and respond to disease threats.

We will develop expertise in community engagement in outbreak preparedness and response. We will emphasise the importance of community systems strengthening and work with partners to develop multidisciplinary approaches to community engagement , informed by anthropology and other social sciences.

We will communicate better. We commit to provide timely information on disease outbreaks and other health emergencies as they occur. We will strengthen our capacity for outbreak and risk communications.

We call on world leaders to take the following steps

First, take disease threats seriously. We do not know when the next major outbreak will come or what will cause it. But history tells us it will come. This means investing domestically and internationally in prevention and in essential public health systems for preparedness, surveillance and response, which are fully integrated and aligned with efforts to strengthen health systems, and included in the scope of development assistance for health.

Second, remain vigilant. This Ebola outbreak is far from over, and we must sustain our support to the affected countries until the outbreak is over, in the face of increasing complacency and growing fatigue. We must continue to maintain a high level of surveillance. Ebola has demonstrated its capacity to spread – it may do so again.

Third, engage to re-establish the services, systems and infrastructure which have been devastated in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. This recovery must be country-led, community-based, and inclusive – engaging the many partners who have something to contribute; including bilateral and multilateral partners, national and international NGOs, the faith community, and the private sector.

Fourth, be transparent in reporting. Accurate and timely information is the basis for effective action. Speedy detection facilitates speedy response and prevents escalation.

Fifth, invest in research and development for the neglected diseases with outbreak potential – diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines. This will require innovative financing mechanisms, and public-private partnerships.

This is our commitment; together we will ensure that WHO is reformed and well positioned to play its rightful role in disease outbreaks, humanitarian emergencies and in global health security.