Slowly dropping out of the headlines, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa – which has claimed over 11 000 lives – is no longer at the centre of international community’s attention.

But two of the most affected countries – Sierra Leone and Guinea – are still battling the disease. Also, Liberia, which had been Ebola-free since May this year, is now confronted with new cases. Ebola is not over.

Our colleague Isabel Coello recently visited Sierra Leone and Liberia and witnessed how the humanitarian effort on the ground continues.

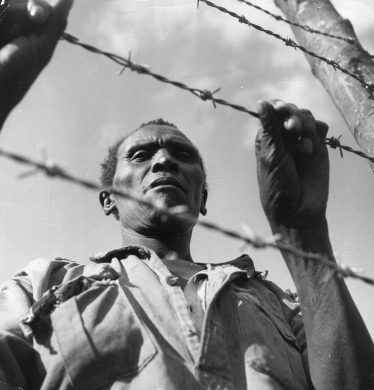

We come across the first health checkpoints along the road as soon as we reach Port Loko, in Sierra Leone. Port Loko is one of the three districts still registering Ebola cases in Sierra Leone – the others being Kambia and Freetown.

When we arrive at the checkpoint, we are asked to step down from the vehicle and walk on a 30 to 50meter-long path demarcated with orange plastic fencing. Health officials say that this path is this long so that people who are ill and too weak to walk that distance can be easily spotted. At the end of the path, there is a bucket with chlorinated water and we must wash our hands. Our body temperature is taken. We have no fever. We can continue.

By the time we reach Kambia district, we have passed six road health checkpoints. Whoever is identified at these checkpoints as fitting the criteria of a suspected Ebola case is retained and turned over to the health authorities for testing. Kambia borders Forecariah, in neighbouring Guinea, where Ebola is also present.

Nye tilfælde hver uge

In July 2015, Sierra Leone registered about 5 to 9 new Ebola cases weekly. The situation is far better than at the peak of the epidemic in late 2014, when the country registered over 500 cases per week.

The ‘Ebola treatment centres’ are no longer full. Yet, bringing cases to zero is proving a difficult challenge. And as long as there is one single case, the outbreak can spiral out of control again.

In all public health emergencies, change in the population’s behaviour is essential to stop transmission. And for this, social mobilization is crucial.

Part of the European Commission’s humanitarian funding in Sierra Leone is delivered to the teams who engage with the communities and raise awareness on how Ebola is spread.

These teams reassure people that seeking early treatment and stopping high risk practices, such as unsafe burials, is the way to end the epidemic.

In Kambia, we meet Kadiatu Bangura, a strong and joyful woman who survived Ebola and who wants to play an active role in helping her community overcome fears and change risky behaviors.

“I want to pass the right messages. Tell people that they won’t be given harmful drugs, nor poisoned food, at the centres” says 32-year-old school headmaster, who was treated in an ‘Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) run by International Medical Corps, one of the organisations receiving EU funding.

“My example shows that it is possible to survive Ebola, that the centres are not killing centres.”

Ingen erfaring med sygdommen

In countries which had not seen Ebola before, people did not understand how the illness come about, nor what the big white plastic constructions – where they saw their family members go in and never come out – were. They denied the disease, buried the deceased without precautions or hid their bodies, and would not send people for treatment.

Awareness has improved but there is still a long way to go. “Some people still question whether the disease is real. They resist the ‘no touching’ policy, being quarantined or not being able to bury their dead the way they always have,” explains Momodu Ismail, who is part of UNICEF’s social mobilization teams.

Usikre begravelser kan sende folk i fængsel

The Sierra Leone government has issued a bylaw declaring unsafe burials a crime. Those who practice them can go to jail. The first exemplary sentences are being delivered.

Some believe that such approach may be counter-productive and will drive people to hide their actions even more.

All deaths must be reported so that a safe burial team comes to pick up the deceased.

The viral load is at its peak in recently deceased bodies. The bodies must be buried in a designated spot with biosafety-compliant procedures.

Quarantines are also imposed in any community at risk of having been in contact with a confirmed Ebola case.

After a 40-minute drive along a bumpy, red mudded road amidst lush tropical vegetation, we arrive at the place where a community is quarantined. Usually communities are quarantined at their homes, but in this case, their village is across a swamp. Should anyone fall ill, it would be difficult to evacuate the patient to a treatment centre, thus exposing everyone to to a tented camp nearby. UNICEF provided them with food supplies, mattresses, mosquito nets, radios, torches, games and educational materials for the children.

Uden støtte fra lokale ledere går det ikke

“People did not want to come here. It’s farming time and they won’t be able to work the land. My role as a leader was to convince them and they followed my advice because I am respected,” the section chief tells Delphine Leterrier, UNICEF’s field coordinator in Kambia.

Leterrier thinks that in order to make behavioural change happen “it is essential to have the support of those who are influential in the communities: village and section chiefs, traditional healers, religious leaders, women… Beyond the message, the messenger must be someone whom the community believes.”

The victim, whose death triggered this quarantine, was a motor cycle taxi driver. Drivers are a high risk group as they are in close contact with many people daily and are asked to transport sick people to healers or health centres.

“When he got sick, he told me not to touch him. I had also heard on the radio ,” says Kadia, the motorist’s wife, quarantined with her one-and-a-half-year-old child. She claims not to have touched her husband when he became sick or when he died. “I am hopeful we will be okay,” she smiles.

Unfortunately, a few days later, her baby got sick and died of Ebola in the camp. She was evacuated to a treatment centre.

The largest, longest, and most complex outbreak of Ebola since the disease was first identified in 1976 is an outright disaster. The countries hit by the outbreak were already among the world’s poorest before Ebola. In what state has the epidemic left them?

“In Liberia – a country still recovering from a 14-year-long civil war – health systems which were already weak are now devastated,” says Audrey Crawford, Head of Programming with the Danish Refugee Council (Dansk Flygtningehjælp, red.). Ebola has affected everyone, both communities with active cases and those untouched.

“Whole communities were quarantined for three months. They lost access to their farms, depleted whatever savings they had, lost jobs or income from trade as borders closed. Ebola really knocked them back,” she says.

With EU funds, the Danish Refugee Council is helping survivors and communities to get their livelihoods back.

Nearly two months after being declared Ebola-free, Liberia has registered new Ebola cases since the end of June.

“We should brace ourselves for the fact that there are going to be more outbreaks,” says the Head of Danish Refugee Council in Liberia, Stéphane Gregoire.

“There is an absolute need to build response capacity and preparedness within these devastated health systems. They need to be more resilient for the outbreaks yet to come.”

The EU, comprising the Commission and its 28 Member States, has mobilized over €1.8 billion in humanitarian aid, technical expertise, longer-term development assistance, investment in research for a vaccine and evacuation provision for international humanitarian workers.