KILIFI, Kenya 6 November, 2017 (UNHCR): Tourists who visit Kenya’s coastal areas of Kwale and Kilifi often go home with intricate ebony carvings.

Many of the talented artists who carve and sell these souvenirs are Makonde, an ethnic group who, until recently, were stateless and excluded from Kenya’s formal job market.

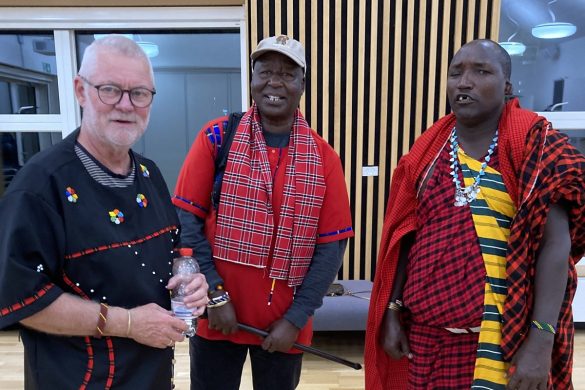

“We were the first carvers to sell on the beach, but they would come and arrest us, saying that we did not have a license to access the area,” said Thomas Nguli, the 60-year-old chairman of the Makonde community. “It was a public beach! Still, we paid middlemen who would give us permits, but then they would run and tell the police who would come and confiscate our meagre earnings.”

The Makonde came to Kenya from northern Mozambique as labourers during the British colonial period and later, as the descendants of exiled freedom fighters and refugees during Mozambique’s civil war.

But despite many Makonde families having been in Kenya since before independence in 1963, they were not recognized as citizens.

Without national IDs, not only did they struggle to earn a living, they could not travel, own property or obtain birth and marriage certificates.

Their statelessness was passed from one generation to the next and Makonde children could not graduate from school or be considered for scholarships.

“De er kannibaler”

A lack of documentation made the Makonde vulnerable to discrimination and constant harassment by the authorities. Thomas remembered one political leader telling a crowd that the Makonde were cannibals. “After that, what hope did we have?” he said.

Discriminatory attitudes filtered down to classrooms. “One of my teachers in school singled me out one day and told the class that I was a Makonde,” recalled Tina Eric, a 22-year-old Makonde woman.

“‘Those are the ones that eat snakes’ she said. I was ridiculed after that. Even those who I thought were my friends did not fully accept me.”

After decades of lobbying, the future for the Makonde, and other stateless minority groups in Kenya, began to look brighter in 2015 when President Uhuru Kenyatta formed an inter-departmental taskforce to look into the issue.

With assistance from UNHCR, the taskforce gathered testimonies and case studies from the Makonde and other stateless groups before issuing a report recommending that they be registered and given citizenship.

But implementation of the recommendations was frustratingly slow and in October 2016, hundreds of Makonde marched from Kwale to Nairobi to plead their case with the President himself.

Kenyatta responded by issuing a directive to give full effect to provisions in Kenya’s 2011 Citizenship and Immigration Act that give people resident in the country since independence the right to be registered as Kenyan nationals.

Onerous requirements, such as showing evidence of having continuously lived in Kenya since 1963, as well as an application fee of 2,000 Kenya Shillings (US$20) were waived for the Makonde. Kenyatta went on to officially recognize the Makonde as the 43rd tribe of Kenya.

A year later, 1,500 Makonde have been registered as citizens, 2,000 of those born in Kenya have been issued birth certificates and 1,200 have received national IDs.

Among them is 51-year-old Amina Kassim who had long eked out a living selling buns and other small items because she could not get a loan or a permit to start a proper business. “Since I got an ID card, my life has changed,” she said.

“I feel like I am born again. Now I am free.”

Tina Eric is also hopeful about her future – that she will find a good job and help to “build the nation” she now finally belongs to. For her younger brother, getting a national ID card has meant gaining the opportunity to qualify for a scholarship to attend medical school.

Skaber håb for andre minoriteter

The government’s recognition of the Makonde offers hope that change may be coming for other minority ethnic groups in Kenya who remain stateless.

Many of them, such as the Pemba community who also live on Kenya’s southern coast, are eligible for citizenship under the provisions of the Citizenship and Immigration Act, but lack the evidence to prove that they arrived in the country or were born there before independence.

A lack of capacity has also made the government slow to register even those who can produce evidence of their residency.

The Pemba arrived from the Tanzanian island of the same name in the 1930s and in a second wave in the 1960s.

Many earn their living through fishing, but their statelessness means they cannot get fishing licenses or loans to buy boats and must fish close to shore where the catch is meagre.

“The biggest problem is the poverty caused by my statelessness,” said Shaame Hamisi, a 55-year-old fisherman and father of 13 who is chairman of the Pemba community.

“I feel belittled and disgraced by the situation that I am in.”

Together with local NGOs and UNHCR, members of the 3,500-strong Pemba community are now mobilizing to encourage the government to recognize them as Kenyan nationals.

The government has shown its willingness to address the problem by extending the deadline by which stateless people living in the country since independence can register for nationality until August 2019.

The Makonde and the Pemba are just two of the stateless minority groups highlighted in a new report, released on 3 November to mark the third anniversary of UNHCR’s #IBelongCampaign to end statelessness.