24 January, 2017 (SciDev.Net): LGBT+ people in Nigeria experience discrimination that hinders their access to health care, including for mental health problems that have been overlooked by many organisations, the Bisi Alimi Foundation has reported based on an online survey.

The survey, published this month (13 January), aims to raise awareness about physical and mental health in Nigerian LGBT+ people, human rights violations against them and barriers to care.

It adds to evidence of a correlation between experiencing discrimination and having mental health issues in Nigerian LGBT+ communities. It also found that the more internalised homophobia one faced, the lower their life satisfaction and therefore the worse off their mental wellbeing.

But access to medical services for LGBT+ people is almost non-existent beyond what NGOs provide. Laws such as the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) bar same-sex partnerships, and even outlaw support for them by non-LGBT+ people. These laws reinforce and maintain limits to medical care due to the stigma associated if health care practitioners treat LGBT+ people, according to the report.

Moraliseret sundhedsservice

Bisi Alimi, founder of the Bisi Alimi Foundation and author of the report, tells SciDev.Net the report reveals the reality of what it means to be an LGBT+ person in Nigeria. “It is not just about the police brutality and harassment, but more importantly, it is the deliberate attempt by healthcare providers to moralise healthcare by deciding who is fit to have access to it and who is not.”

The online survey contained 63 questions about physical and mental healthcare, public perceptions and reactions to gender identities and sexualities, harassment and violence, daily life experiences related to sexual orientation, legal issues as well as demographic information.

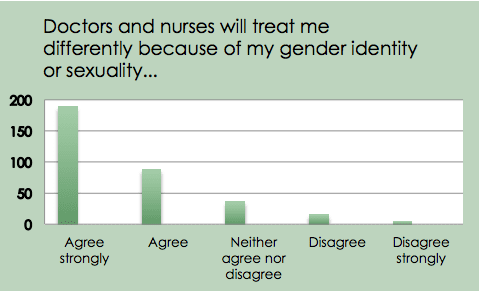

Of 446 LGBT+ Nigerians who responded to the survey, 44 per cent did not seek medical care when they had a physical health problem. Alongside practical reasons such as clinic opening hours or distance, the biggest concern reported was feeling unable to trust healthcare providers.

Of the 22 per cent who did seek medical care, many (12 per cent) were told their problems were their own fault, experienced verbal abuse from doctors or nurses (12 per cent) or even rough physical treatment (7 per cent). The report states that this range of negative experiences is directly related to the cultural attitudes imbued by legislation against LGBT+ people, as well as a lack of training, supervision and awareness among healthcare staff.

William Rashidi, founder and director of the Queer Alliance Nigeria, a human rights, health advocacy and support group, told SciDev.Net that this data “contributes to … gradually forcing policy makers to begin to consider the toll of discrimination on a wider platform”.

Researchers have failed to detail the toll of discriminatory laws on healthcare and people’s psychological well-being, says Rashidi — the focus has been on sexual health and HIV for too long.

Appel til NGO’er

The report urges organisations to train and protect healthcare staff, to increase services that cater to wider health needs and to extend services to lesbians, bisexual women, transgender people and those with disabilities.

These actions, it says, are in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals to reduce inequalities and promote social, economic and political inclusion.

It also calls for the media to share more specific guidance for LGBT+ people on when and where to seek health care, and what to do if there is no access so as to live more comfortably until attitudes change.

While Rashidi agrees the recommendations are positive, he calls for action within the health sector specifically — institutions such as the Nigerian Medical Association, the National Agency for the Control of AIDS, psychiatrists and psychologists.

“The media has the power to educate and create change, but they also need information from the health sector,” he says. “Whilst not perfect, the data is a good start to discussing mental health issues within the context of sexual orientation and gender identity. This is far overdue.”