300.000 hektar ny skov er oprettet i Chile siden 2000, men bagsiden af den solstrålehistorie er, at den nye skov er industrielle tømmerplantager, mens oprindelig, vild skov bliver fortrængt, og det forringer både biodiversiteten og forholdene for den oprindelige mapuche-befolkningen.

Det skriver miljøportalen Mongabay mandag.

At first glance, the statistics tell a hopeful story: Chile’s forests are expanding. According to Global Forest Watch, overall forest cover changes show approximately 300,000 hectares were gained between 2000 and 2013 in Chile’s central and southern regions.

Specifically, 1.4 million hectares of forest cover were gained, while about 1.1 million hectares were lost.

On the ground, however, a different scene plays out: monocultures have replaced diverse natural forests while Mapuche native protesters burn pine plantations, blockade roads and destroy logging equipment.

At the crux of these two starkly contrasting narratives is the definition of a single word: “forest.”

Tømmerplantager må ikke forveksles med skov

According to a recent study in Landscape and Urban Planning, timber plantations expanded by a factor of ten from 1975 to 2007, and now occupy 43 percent of the South-central Chilean landscape.

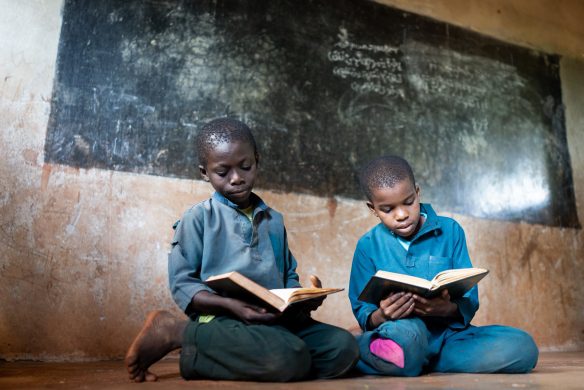

Co-author Dr. Cristian Echeverría predicts further deforestation and forest degradation in accessible parts of the landscape.

“We need drastic changes [in order to] attain a sustainable future for our forests,” he said. “State subsidies, payment for ecosystem services, improved education and national reforestation programs will all be needed.”

While the confusion surrounding the definition of “forest” may appear to be an issue of semantics, Dr. Francis Putz of the University of Florida warns otherwise in a recent review published in Biotropica.

“While I believe that high intensity, low diversity, industrial tree plantations have many roles to play, confusing them with forest is a fundamental problem of the highest order,” he said.

The problem lies in the environmental services that these land uses provide.

Monoculture plantations are optimized for a single product, whereas native forests offer a diversity of services such as water regulation, hosting biodiversity, and building soil fertility.

Putz cautioned, “if plantations are accepted as forests, then there is nothing wrong with replacing natural forests with monocultures.” This murky definition of forest has robbed the Mapuche of their lands, and threatens to further endanger Chile’s remaining native forests.

Putz explained, “in the case of Chile, it’s relatively easy [to distinguish between plantations and forests] because most of the plantations are of an exotic species.”

“Society, and certainly decision-makers, need to demand clarity on this issue, and the point that plantations are NOT forests needs to be made repeatedly,” he said.