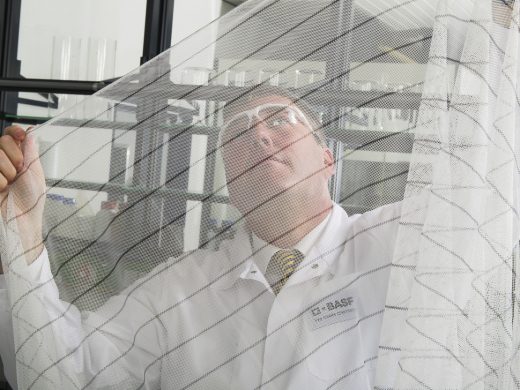

LONDON, 3 August, 29017 (SciDev:Net): The World Health Organization (WHO) has provisionally recommended the use of a new generation of insecticide-treated mosquito nets — a step forward for the prevention of malaria. Interceptor G2, developed by the German chemical company BASF, is treated with a blend of two classes of insecticide.

According to articles published in the Malaria Journal and PLoS ONE, the first is alpha-cypermethrin — known as a pyrethroid, this is the insecticide currently added to mosquito nets. Interceptor G2 also incorporates chlorfenapyr, a type of insecticide typically used in agriculture and to combat pests in urban environments —it had not previously been used to prevent disease.

“We observed that Interceptor G2 systematically eradicated a significant proportion, around 75 per cent, of malaria vectors that had become resistant to pyrethroids,” Corine Ngufor, a researcher at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in the UK, and one of the authors of the study, told SciDev.Net.

According to Egon Weinmueller, who is responsible for public health business at BASF, Interceptor G2 “is more appropriate for use on the netting mesh and the polyester used in nets”. He said that its insecticide formula is longer-lasting than that used in currently available nets, and this means the nets are more effective and safer.

“However”, adds Weinmueller, “its key characteristic is that it acts in a completely different way to conventional public health insecticides; this makes it an ideal tool to combat insecticide resistance”.

It works by affecting the mitochondria of cells and the mosquito’s ability to produce energy, he explains. “Because it is metabolised by the insect before it starts to affect the production of energy, it is very difficult for the mosquito to develop resistance and transmit it to its offspring.”

African trials

Tarik Jasarevic, a communications officer at the WHO says the agency made its recommendation after “the results of Interceptor G2 trials carried out in laboratory conditions and on the ground at a small scale were discussed by the WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme (WHOPES) when it met from March 20-24 this year”.

The trials were conducted in several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa including Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania.

Ngufor is one of the researchers who worked in Benin, under a collaborative project between the LSHTM and the Cotonou Centre for Entomological Research (CREC).

“The nets were tested for effectiveness against mosquitos both before and after having been washed, and in laboratory trials,” she explained for SciDev.Net, adding that this new net continues to work even after having been washed up to 20 times.

Ngufor said the nets were tested in households in the south of Benin, where mosquitos are known to have become resistant to existing insecticides.

Similar results from Burkina Faso were described in a separate study where researchers carried out trials in experimental huts with nets treated either with alpha-cypermethrin, chlorfenapyr, or a blend of the two insecticides.

The research team concluded that “among all the nets trialled, the combination of chlorfenapyr and alpha-cypermethrin led to better mortality [of mosquitos] after 20 washes”. They noted, however, that the nets do become less effective with washing.

“This new type of insecticide-treated mosquito net will remain effective for at least three years,” says Weinmueller.

Fighting resistance

The production of Interceptor G2 is the end result of a decade of collaborative research that brought together BASF, the LSHTM, the CREC and the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC) at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Their aim was to solve the problem of growing resistance to the insecticides currently available.

Ngufor says that the research team faced numerous challenges from start to finish. “Chlorfenapyr is a new insecticide in the context of vector control and current methods for the evaluation of products [that contain it] are not necessarily appropriate.”

The team had to be creative and patient, while remaining within WHO guidelines, in order to fully explore Interceptor G2’s potential, according to Ngufor.

According to Weinmueller, there are no known cases of resistance after 20 years of using chlorfenapyr-based formulations in agriculture and to control urban pests.

“We can’t be 100 per cent certain of course, but scientists believe that there is little chance of vectors becoming resistant to the active ingredient,” he says.

More testing ahead

Despite the promising results, the researchers recognise that no product can be guaranteed to work in all circumstances.

And the WHO is not yet entirely convinced of Interceptor G2’s viability, and emphasises that its recommendation is ‘provisional’.

Jasarevic notes that the provisional recommendation is based only on tests of it “as a mosquito net treated with a long-lasting pyrethroid insecticide”, noting that the impact on public health of the addition of chlorfenapyr has not been evaluated or established yet.

“In order that we can ascertain the combined effect of Interceptor G2 on malaria and public health, BASF has been asked to outline its plans for epidemiological trials and to share the results of these studies so that a further review can take place”, Jasarevic told SciDev.Net.

While working to produce the additional data required, the German chemical company is already taking steps to distribute the product free of charge by the end of 2017 in countries where the disease is endemic.

This article was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa-French edition.

Artiklen bringes under Creative Commons-licens.