RUBAVU, 14.10.2014: Nairobi kalder. Det er syv år siden sidst. Abstinenserne begynder at melde sig.

Elsker-hader den by, der rummer alt, man kan elske-hade i Afrika: et mikrokosmos af hjerteskærende forskel mellem en lille rig elite og de fattige masser, et støjende inferno af kontraster, skræmmende og fascinerende på en og samme tid.

Der er ikke andet at gøre end at drage fra Rwanda-bopælen i Rubavu op til Kigalis Internationale Lufthavn.

Her hopper jeg ombord i en Kenya Airways, flyver til ”the City in the Sun”, hvor jeg lander en time senere i bælgravende mørke.

Jeg har store journalistiske planer for besøget. Jeg skal samle kenyanske stemmer, skal jeg. Snakke med høj og lav, politikere, meningsdannere, erhvervsfolk, fra over- og middelklassen via taxi-chauffører til folk i slumkvartererne.

Derhjemme i Rubavu har jeg skrevet til organisationer og personer og bedt om møder og interviews, bl.a. med præsident Uhuru Kenyatta.

Men han svarer ikke. Kan man nu forstå det?

Kontakt

Mere held har jeg med den tidligere chef for Transparency International i Kenya, John Githongo, der i 2003 blev udnævnt til Minister for Regeringsførelse og Etik af eks-præsident Mwai Kibaki.

Githongos opgave var at rydde op i den massive korruption, et af Kibakis valgløfter.

Men Githongo gjorde arbejdet så grundigt, at han modtog dødstrusler og i 2006 måtte flygte i eksil i London.

Arkivfoto: David Mbiyu (Creative Commons)

I 2008 fik han frit lejde tilbage til Kenya, hvor han grundlagde et par NGOer, og er i dag involveret i snart sagt alt, hvad der kan kravle og gå af organisationer, der har noget med ”civil” at gøre, er en eftertragtet debattør og kommentator.

For mange er han den store helt, der i stedet for at berige sig sammen med eliten forsøgte at gøre noget ved korruptionen, som ifølge Institute of Certified Public Accounts of Kenya årligt dræner landet for 4,5 milliarder kroner, og som fordyrer leveomkostningerne for kenyanerne med mindst 15 procent.

Andre er mindre begejstrede. Det gælder en tidligere kollega, ex-Internal Security Minister Christopher Murungary, der har trukket Githongo i retten for bagvaskelse i forbindelse med undersøgelserne i 2003-4.

Jeg sms’er med Githongo fra en taxi i en vanvittig forstoppet trafikprop på Ngong Road. Han er i retten for at forsvare sig, men han foreslår at vi mødes dagen efter.

Han udsætter.

Næste dag sender jeg en ny sms fra en ny trafikprop. Det sker en syv-otte gange, indtil jeg ti dage senere er retur i Rubavu, hvor Githongo i stedet giver sig tid til svare skriftligt på mine spørgsmål.

Det følgende er et sammendrag af en længere e-mail-korrespondance. Det foregår på engelsk, for ikke at knuse nuancerne:

En ubehagelig situation

U-landsnyt (ULN): In one of your essays you talk about the Kenyan “software” that went out of sync in Westgate, triggered by soldiers/police that looted the premises, and then you move on to say that Kenyans are not vultures. Please elaborate.

JG: We Kenyans have always believed in our own exceptionalism: we have not had multiple coups, have generally managed the economy well and not slid into civil strife that has affected so many of our neighbors since independence. Westgate was both a wakeup call and chickens coming home to roost. Combined with the violence of 2007/8, Westgate ended the myth of Kenyan exceptionalism. It is an uncomfortable condition.

ULN: The present political climate in Kenya with politicians advocating for a new referendum. What is your take?

JG: Politics have failed. We keep on going to the polls every five years and end up recycling the same bunch of tired politicians and the new ones are quickly sucked into the morass of thievery that characterizes the top. Partly as a result, the capacity of citizens to hold their leaders to account is truncated. The agitation for yet further constitutional reform is derived from the sense that we changed forests (with the new constitution) but the monkeys have remained the same.

I believe that when Africans opted for political pluralism after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the wind of change blew across the continent, they were not embracing a system of governance they fully appreciated and understood. The primary desire was for accountability: that leaders stop stealing from their citizens.

The most dramatic expression of the new system was the open, free and fair ‘general election’ in which a multiplicity of parties could compete. When the results of multipartyism proved disappointing because power continued to be wielded by entrenched elites who enthusiastically exploited the cleavages in African societies in order to hold on to power, agitation for constitutional reform kicked in.

Ulighed

ULN: You have said that the biggest challenge to Kenya is not “tribalism” but “inequality”.

JG: I firmly believe so. We have democracies run by gangsters, and economic growth without equitable development. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the triumph of the ‘Washington Consensus’ with its neo-liberal economic model we have lacked the courage to think of a new model for fear of being branded ‘socialists’ after socialism ‘failed’.

And yet the new reality is faltering as well. The economic crisis in the West in 2007/8 demonstrated the extent to which corruption, casino capitalism, conflict of interest, and the worship of greed are central to the capitalism that has been dominant for so long. Now we are not even sure the environment can climatically endure this model of ‘development’.

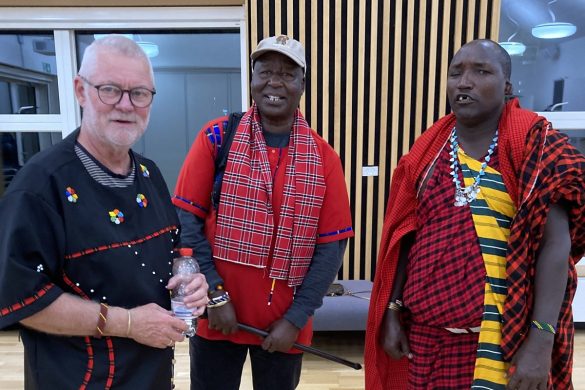

Foto: Lars Zbinden Hansen

Inequality in Kenya cannot be eliminated totally. However, it can be mitigated via affirmative action towards t, those with power use it for the wider good to the greatest extent possible.

Sofistikeret korruption

ULN: You have stated that “Kenya is more corrupt than other countries”. Is that statement still relevant?

JG: Kenya has ranked in the bottom 25% of the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International since the Index was launched in the 1990s.

In Kenya graft is episodic: on the surface governance institutions work but especially around election time elites extract/steal/corruptly acquire huge sums from public coffers ostensibly to fund political campaigns.

Kenya and a few other countries are unique in that we have a sophisticated services sector that allows corruption on a grand scale always involving businessmen, lawyers, accountants, bankers, bureaucrats, politicians and members of the security services.

Graft in Kenya has been normalized. It’s gone white collar. It’s no longer Mobutu types raiding the Central Bank, Emperor Bokassa crowning himself while drunk.

Corruption now more closely resembles its Western counterpart: hedge fund managers cooking up complex financial instruments, crooked lawyers and judges, smug bankers, land speculators.

Corruption wears Gucci today, speaks multiple European languages and has the Western education to rationalize its absurdity.

Ubuntu versus individet

ULN: A quote from you: “We” see “ourselves as individuals”. Isn’t it claimed that Africans are communal as opposed to individualistic westerners?

JG: You are right. Ubuntu says: I am because we are – this is the African way. Decartes said, I think therefore I am. Right now we are as Africans living a contradiction of trying to be both at the same time.

We are at once ‘generation me’ and at the same time part of the collective we of kinship. The contradictions that arise from this are most evident in the urban areas where for the first time in history more Africans live than in the rural areas.

A few leaders have been bold enough in a structured manner to attempt to create a harmonious coexistence between the communal we and the ‘modern me’ of the city – Nyerere in Tanzania, Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso for instance.

Middelklassen

ULN: Is there really a “booming” African middle class?

JG: The middle class in Africa is there and growing, but it is hugely overrated. It is defined by its capacity to consume by most observers. It is fragile, however. “Boom’ is an over excited word.

ULN: Is the Kenyan economy booming? The latest figure says more than 5 % of GDP.

JG: GDP is nonsense. What does it mean to be booming with 5% yet in entire swathes of the country simple diseases are decimating populations? What does it mean when entire populations/regions live in fear of their lives? The Kenyan economy is booming for a few – bankers, corrupt politicians, lawyers, accountants.

Den gule fare

ULN: “China in Africa”. Please give us your take. Is the “invasion” good for Africa? How does it affect the African-European (and US) relations?

JG: Remember the Westerners came here as ‘invaders’ too driven by a desire to extract. The Chinese are no different, only more blunt about it. They have not come accompanied by missionaries enlightening the ‘natives’.

The Chinese juggernaut has been so huge that it would seem the West has given up this battle and is standing in line behind the Chinese waiting to sign deals before they get left too far behind. The moral authority of the West to opine on governance has been undermined by the Guatanamos, Abu Gharibs etc. However, the fundamental freedoms enshrined in the governance systems of the West are deeply compelling to Africans: freedom of speech, association, freedom of expression etc.

ULN: Your take on foreign development aid?

JG: Development aid’s relevance is ending. At independence, all African countries were battling the same things: ignorance, poverty and disease. Considerable strides have been made on all fronts and foreign aid has played its part in these achievements.

In truth, improve governance and head towards eliminating corruption in its systemic forms and countries like Kenya don’t need a dollar of foreign aid. So the need for aid is a state of mind as well – a dependency.

Magten rådner

ULN: Another quote from you: “UN will look very different” in the future. Please elaborate on how you think a change will come about.

JG: Maybe it’s wishful thinking on my part. The kind of asymmetrical conflict we have witnessed since the fall of the Berlin Wall and especially after 911 means that the world’s most powerful countries are increasingly challenged by small, mobile, deeply committed, ideologically intolerant forces that cannot be destroyed by bombs, ‘surgical strikes’ and even the military industrial complexes of the world’s most powerful nations.

The nation states that sit on the Security Council will hold on to the power they wield jealously. The relevance of that power and the current means of projecting it conventionally are declining in relevance. Recent events in the Middle East are a testament to this. As Moses Naim observes, ‘power is decaying’.

We have also seen ‘the rise of the rest’: the BRICS in particular confident enough to challenge the contradictions, double standards, hypocrisies of the Washington consensus. The mythical omniscience of the West’s security services has been challenged by events, mistakes and blunders: from missing 911, being massively hoodwinked by Pakistan, Edward Snowden’s mega leaks, Wikileaks etc.

Gone are the days when the US president could nod and a democratically elected Chilean president would be overthrown, an Emperor installed in Iran, a premier murdered in Zaire and replaced with a puppet. The world is smarter and more sceptical of the old powers.

Et ubesvaret spørgsmål

Der var mange flere ord i e-mail-samtalen med Githongo. Blandt andet spurgte jeg til hans mening om angivelige unøjagtigheder i bogen om ham: Michela Wrong: ”It’s our turn to eat. The story of a Kenyan Whistleblower”, som jeg kom under vejrs med i Nairobi.

Men han gled af, svarede ikke på det (gentagne) spørgsmål.

Den historie bliver den næste i serien om gensynet med Nairobi – læs den her