A gun-toting, loudmouth mayor and the son of a former dictator look set to win the two top posts in the Philippines’ May 9 elections.

Rodrigo “Digong” Duterte, mayor of Davao City in the southern Philippines, has a 32 per cent lead over the four other presidential candidates, despite allegations of secret multi-million dollar bank accounts and a line in offensive rhetoric.

Meanwhile Ferdinand Marcos Jr, the only son of the dictator whose 21-year rule ended in 1986, has long been the consistent favourite for vice-president.

Both are campaigning as anti-establishment figures with the leadership skills and party capacity to improve people’s lives in a way that incumbent Benigno Aquino III, for all his assurances of change and equality, has failed to do.

The country’s two bloodless uprisings since martial law ended have not brought the social and economic change they promised.

Although the economy has improved during Aquino’s six-year term, the popular perception is that only the rich have benefited.

Many people still subsist on an income of around two dollars a day and a December 2015 survey showed that about 11 million families considered themselves to be poor. In Manila, families said they needed a monthly income of 500 dollars to lift themselves out of poverty.

The lack of a social safety net has driven more than 10 million Filipinos to seek a better future abroad. These workers often suffer abuse and discrimination in their host countries, and the break-up of families has had its own impact on Filipino society.

Corruption also remains a huge problem.

Unorthodox leaders

It was the so-called People Power uprising of 1986 that catapulted Aquino’s mother Cory into office. But her son’s promise of truly transparent government when he took power in 2010 has failed to translate to real, tangible change in the eyes of most ordinary Filipinos.

Claims of accountability were notably shaken by a 2013 scandal in which some 50 legislators and fake NGOs allegedly siphoned off 211 million US dollars of legislative funds.

In contrast, Duterte, and to some extent Marcos, are both seen as unorthodox leaders with the ability to deliver results.

Significantly, both have also been endorsed by the Iglesia Ni Cristo (INC), an influential religious sect with a track record of being able to deliver the votes of its two million followers.

Confidence in a strongman

Duterte’s tough image has led to nicknames such as The Punisher and Duterte Harry, a reference to the 1970s hit film starring Clint Eastwood.

This has apparently endeared him to the public, especially among middle-income families and the poor.

Political foes have attacked Duterte as a thug, a womaniser and a parochial politician lacking in any presidential diplomacy. One television ad run by his opponents was simply a video montage of controversial statements Duterte has made on topics such as vigilante killings, rape and the Pope.

But many Filipinos appear willing to tolerate such characteristics for the change that they badly want to see, particularly success in the war on crime.

“He has the guts to stop corruption and crime in our country. He did it in Davao. He could do it for the whole Philippines,” said one taxi driver from the central Philippines – the region of Aquino’s anointed presidential candidate Manuel Roxas.

Roxas has promised honesty, integrity and diplomacy under his watch. But this has failed to convince many who are desperate for a solution to their hunger and joblessness.

The international media have noted Duterte’s similarities with US presidential hopeful Donald Trump, pointing to their unexpected popularity despite their controversial statements.

In Trump’s case, these have been mostly on immigration issues. For Duterte, pronouncements on crime and human rights have won the column inches.

Recently, Duterte joked that he “should have been first” in the gang rape of Australian missionary Jacqueline Hamill inside a Davao prison in 1989. She was then murdered.

Despite widespread outrage and complaints from the Australian and US embassies, Duterte remained unrepentant.

Talks with Communist party

Duterte has also leveraged his security credentials, both as a mayor tough on crime and as the only candidate from Mindanao, the southern Philippine region that is home to the longest-running insurgency in Asia.

The conflict between the government, Muslim secessionists, communists and other armed groups – including Manila-backed warlords – has left the region unstable and impoverished despite its rich natural resources.

Supporters feel Duterte has a clear grasp of the complex situation and the genuine desire to put an end to the decades-old conflict.

Indeed, he has already held talks with Communist party leaders and promised to immediately declare a ceasefire and restart negotiations if elected president.

Marcos, also popularly known as Bongbong, has similarly exploited public disillusionment with the pace of change to help boost his chances of returning to the presidential Malacanang Palace. If he wins as vice-president, Bongbong is a step closer to running for the top job in 2022.

To many, especially to the thousands who suffered during his father’s rule, this prospect is both dangerous and shameful.

According to Amnesty International, about 70,000 people were jailed, 34,000 tortured and more than 3,000 killed during the elder Marcos’ 1965-1986 rule. Another 800 were disappeared.

Those in the Marcos’ circle enjoyed lavish lifestyles as the country languished in debt and poverty.

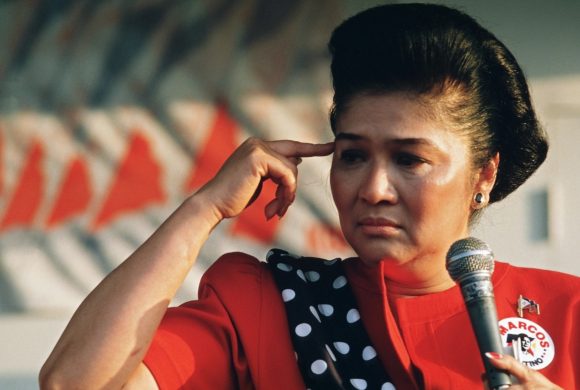

Despite this, Bongbong’s mother Imelda, infamous for her collection of 3,000 shoes, and his sister Imee also have flourishing political careers.

The sins of the past

As well as a new president, the archipelago’s 54 million voters will choose a vice-president, 12 senators and local officials such as mayors.

Imelda is running for a third term as district representative of the Marcos home province of Ilocos Norte in the northern Philippines, while Imee is seeking re-election as Ilocos governor. Both are unopposed.

Survivors of martial law – some of whom are also running for national and local positions – have been campaigning hard against Bongbong’s return.

They have tried to counter his claim that he knew nothing of the cruelties of the nine-year period of martial law, which ended in 1981.

A fierce primetime TV and social media campaign has featured testimonies of victims of martial law who called on Marcos to return his family’s ill-gotten wealth. The hashtag #NoMoreMarcos emerged a week before the elections.

But Bongbong’s anti-establishment agenda seems to have gained traction, especially among twentysomething voters who know little about his father’s dictatorship.

All this seems to be disturbing evidence of the Filipino’s tendency to easily forgive and forget the sins of the past.

In a country where democratic processes have repeatedly failed to improve ordinary people’s lives, the public appears to be favouring strongmen who bring results – no matter the consequences.

Rorie Fajardo-Jarilla is IWPR’s Philippine Country Director

Læs flere artikler fra IWPR's tema Global Voices her