Af Julie Damgaard, U-landsnyt.dk

Efter tre ugers arbejde i VerdensKulturCentrets café holder den senegalesiske kunstner Kiné Aw i dag de-fernisering på en udstilling med nye værker.

U-landsnyt.dk mødte Kiné Aw første søndag i advent ved en juleworkshop for børn på Statens Museum for Kunst for bl.a. at høre nærmere om det at være kvindelig kunstner i et traditionspræget, afrikansk samfund.

What is going on here at the National Gallery today?

In my program I was supposed to do a workshop with children. When asked to attend I was thinking I was going to do a painting performance with the children, but because they changed the idea, because they say it’s Christmas time , that’s why we are just having fun, relaxing, just doing some amusing stuff with the children.

So you are doing some sculptural work?

Yes, it’s just structuring something, making something ‘grow up’ and we’ll see what it’s going to be.

And you are working with found materials?

Yes, all these materials they gave me here, materials for children. It’s about trying to get the liberty that the children have, trying to ‘grow up’ something …

I believe it’s the second time you visit Denmark?

It’s my first time in Denmark, but I’ve been to Europe several times.

Have you had a chance to visit museums, galleries or project spaces while you have been here?

I was in a very interesting museum, Louisiana, and I am going to take another look around the National Gallery today if I can make it.

I went to a place I really appreciate, Christiania. It’s interesting because I feel that it’s an artist community. We have something like that in my country. Not really like you build it here, but it’s a village of art and I work there. It’s professional, contemporary artists living and working there. They collaborate and have their own structure. Christiania reminds me of this village.

This is what I’ve seen so far, but we have more to do in my program over the next week.

Have you seen something that especially impressed you?

Yes, in Christiania I was introduced to some artists, very interesting. I liked the works but I’m more interested in how Danish people think about art. What is significant for them in contemporary art?

I was very impressed to see that they have some great artists, but why I am here – the program – is to try to let people know that Africa has some great, contemporary artists. In my understanding many Danish people think Africa is one country. No – Africa is a continent. So much culture.

Here, people think that Africa is just a poor country, that people are just trying to get money. Yes, in some parts people are poor. But at the same time people live in the contemporary world, we have some great journalists, great medicine, great philosophical people, and we have great artists and cultural people. So much stuff that people has to know.

I hope people are going to be interested in what I’m doing. I am telling people who I am and what I’m doing.

We are here – the other Africa – and people need to know about us, to open their eyes. Right now the world is a globalised place. We should be connecting, because the world is connecting now via the internet, the phone. People don’t have to close their eyes, they have to open them.

I’ll tell you something, I travel a lot, not just in Africa but also in the US and in Europe. How the contemporary African art is growing up is amazing. I miss to see this here and wish that people would open their eyes.

What do you consider the biggest difference between contemporary African art and contemporary European art?

The difference has to do with what we feel when working on our art. Because art is a feeling. Art is something you live with, it is an expression. An expression about your daily life maybe, an expression about what you want inside your community.

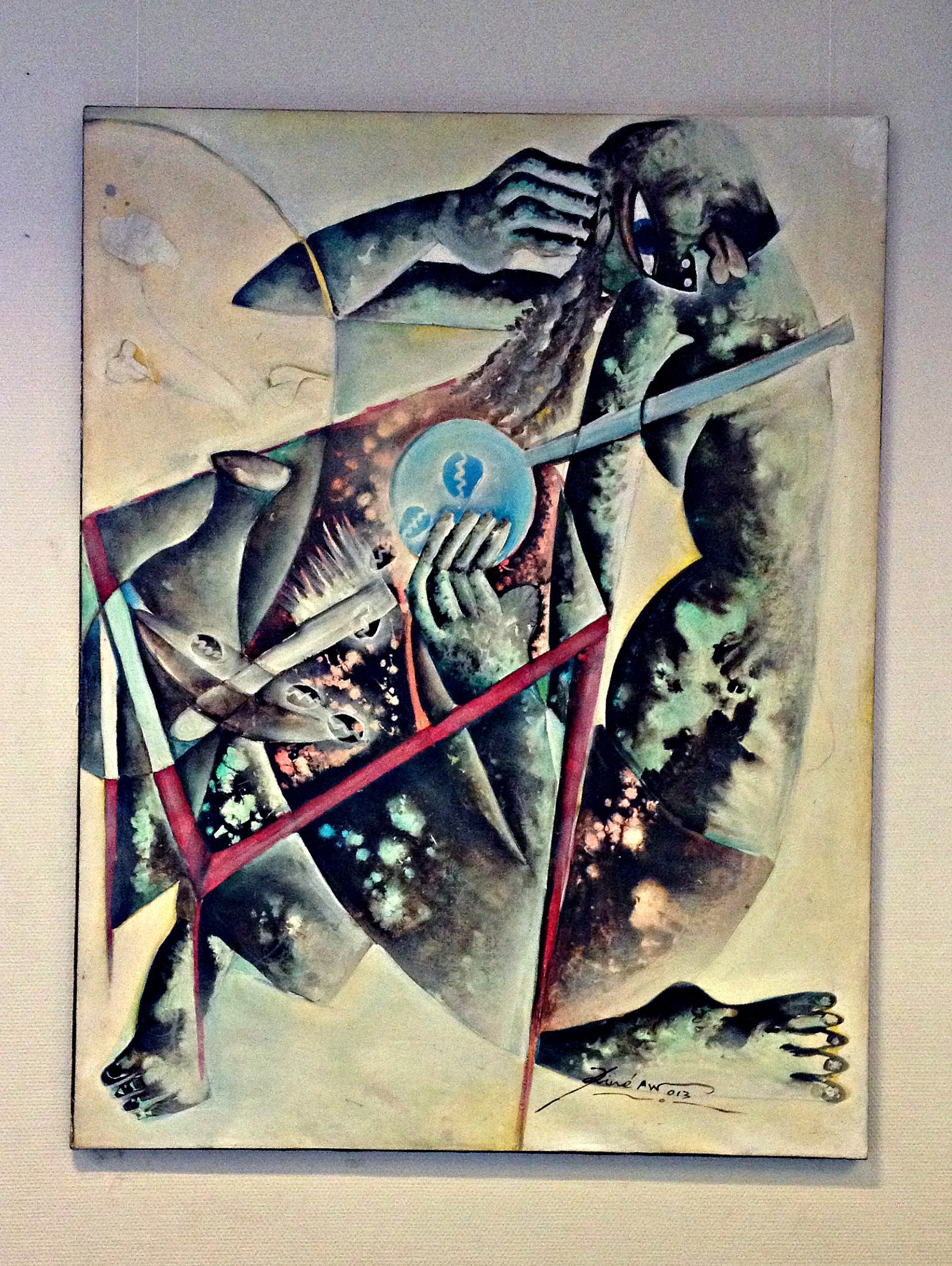

For my part, my work is about the African woman. The expression of the African in both bad and good ways; anything that comes up in my mind, including my culture. You cannot work without something just near to you and near to your spirit. The difference is just about how to express it in your own view, from where you are.

My work centres on my daily life, my tradition. My context is the daily life of African women in a contemporary world – and in a traditional one.

I think an artist, wherever he or she is, works on a feeling. An expression about your future or your past, about where you are. To do the comparison between contemporary African art and European art, that’s going to be so difficult.

How did you get into art to begin with?

I graduated from the National Art School in Dakar – we have a great National Art School – but also I was doing art before. When I was younger, though, it was just for fun, but in 2000 I decided to try and get into the National Art School. They told me, however, that they were closed for applications and that I had to wait until next year.

Then I went from 2001-06, and I graduated. People now recognize my work as a ‘Kine Aw’.

Did you always do painting?

Yes, always. I sometimes do small sculptures. But still now I am more focused on the painting. All the technical details. I’m an artist working with mixed media. Through my texture I try to get a certain expression. Mixing oil painting and acrylic painting is giving me an interesting expression.

Right now I am like in a laboratory in my studio and I cannot say I get something, ’cause art is never done. It’s just research, research, research.

You mentioned the woman in your art, but can you elaborate a little bit more on what inspires you on a daily basis?

There is so much stuff to say about the woman in the daily life. I am also a woman living in the society. We are contemporary, modern, but we are also traditional. We have so much contrast, it’s amazing. To be an artist and to be a woman, it’s not easy.

How I express the woman in my work is through different subjects, like the mother and child, which is one of my favourites; and the woman with the music, like the kora-players [koraen er et harpelignende strengeinstrument fremtrædende i vest-afrikansk musik]. The look into the context of the woman in my society right now – we have to live traditionally, but also we have to live in a modern way.

When I start something it’s like a rhythm, I don’t know exactly where I’m going but I know I will work on the woman. But what will she express? When I finish, the painting is going to tell me. The subject of the African woman will never be boring, and I will never be tired to work with it. There is so much to say as you can tell from my painting. It can be the sadness, the happiness, it can be everything.

You touch about the theme of the African woman’s characteristics. What are those characteristics?

In my society I’m like an actor, but I’m also a spectator. I’m not just acting like everybody is doing in their daily life, I also see the good and the bad. The reason I’m lucky is because I’m an artist and I have the freedom to express this in my painting.

As a woman you are supposed to be a good woman, which means – very importantly – to be a good wife and to be a good mother, to stay in the family, to have a good job. It’s hard to be an artist, but being both a woman and an artist means you are not like the other women in society. The concept is not very easy.

How does woman work in this modern society and at the same time be a traditional wife? How to balance these two things?

The reason I’m fascinated by the subject of the woman with the kora, is not just because I like the form of the kora and the sound of the instrument, but also because the woman with the kora is an artist. It’s very unusual to see an African woman playing the kora. It’s not like seeing a female painter – it’s not allowed. But I like to express it because the concept is nice, beautiful. Wonderful even.

In my society you more often see the woman singing than playing. Why I like to talk about African woman is because even though Senegal is a small country we have so many ethnicities, we don’t speak the same language even, and each ethnic group has its own traditions, for instance when it comes to marriage: which ceremonies the young woman has to go through before getting married, before entering the house of her husband.

People ask me why I do not work with the man as a subject. That’s because I am wife, I am woman, I am mother, I am sister. I am actor and spectator and have so much I want to say, I cannot finish it.

You have said “I do not base myself on the details of figurative as such, but rather on essence.” What does this mean, this essence?

When you see this girl, how she is sitting down, you see the expression of a girl sitting down, doing something. But I’m not focusing on expression, exactly, meaning the figurative depiction of everything she is doing. Instead you will feel it.

The essence is about how I think it is. I try to let people just feel something. It’s like in the cubist works. It’s not a real perfect, figurative finish. You see everything, the eyes, the line, the air, but first and foremost you feel something – in the way I want you to feel.

You can see a girl sitting down, doing something. But in my unique representation. I’m not just saying I want to do perfectly, no matter what. No, through my destructuring I try to make structure. It’s a ‘des-organisational ordering’.

I destructurate like in cubism, but you can see in the expression what I want to do – and you say “she looks sitting” …

How do you start a painting? What’s your process like?

That is interesting. If I do a workshop, it’s different, but working in my studio, the first step – before taking my brush – can take three days. When I finish the painting you see the first step in the painting. It’s a base for me.

Because I mix oil and acrylic, I have this first step to do, where I mix the two, and it takes not just 50 minutes to be dry. You have to wait. My process is very particular, but I like this. When I finish my work you can feel the process. I can have a subject in my mind, but the finish you never know. I don’t ever really know exactly that this color will be here or that this color has to be on the left. No, it’s like magic.

Art has two sides to it – the anecdotal and the technical. The subject is freer than the technique, it’s slowly ‘growing up’. You make the technique and the subject come together to have something happen.

You use rather untraditional materials like tar and untraditional tools like your breath. What does these tools and materials mean in your work?

My studio is like a laboratory. The first three days I have to wait. My first step is the mixing together of paints and I have to wait until they dry. Mixing tar in the acrylic gives me a great effect. After finishing the canvas you can almost feel it. It’s not just painting for painting’ sake. I try to have an interesting technique in my painting. Also I use my breath. It gives a special effect.

After the first phase I take my brush and make my line, my ‘personage’, the figure emerges and after this I try to make a combination of all of this. So it’s not only a painted figure, but a figure with something ‘growing up inside it’.

I don’t only use the techniques given to me in art school. There is more. For me it’s not just about respecting the academic, what we study in school, but to be curious about what I do. To know the teachings of the art school about how to get the light and dark right for instance, and then do it in your own way.

You use your breath to create an effect in the painting, but at the same time it seems to me that you breathe life into your painting…

That’s very interesting. One day I had friend visit me and when he saw me doing that, he started filming. I explained to him that the time spent in my studio allows me to do my own research, like when I use my breath.

When I first saw your paintings it seemed to me there was an inspiration from early European modernist painting, like the proto-cubist work of Picasso with its references to African masks. Is this actually an inspiration to you and, if so, is it then a way to, say, reclaim your African heritage?

Often people come to my studio and say “oh, my god – you work like Picasso.” Maybe they don’t know, maybe they just assume I am an artist imitating another artist. No, I’m African, the line is mine. It’s my tradition: the mask, the so-called tribal art. Cubism – that’s us. How can people tell me to stop doing this?

Picasso was a great artist that I really respect, everybody knows from where he got the inspiration for his cubist work, and they have to understand that this inspiration … – is me, it’s my culture. I cannot stop it.

If you go to see my exhibition, you know I work with cubism, but differently. I don’t think about anything, I just think the line: how to use the line to shape something, like a woman. Cubism is not just for Picasso, I do what I feel. I express my own view with this line. It’s my own tradition and I cannot do something else. I cannot paint naturalistic. My point of view about the cubism is inside me.

You are taking up different subjects, among others the mask. What does this specific subject mean to you?

Everybody sometimes carries a mask, like when you are with your family. How you are inside your family is different from how you are at work.

But we also have some spiritual things to say about the mask. In West Africa we are more Muslim people, but also have animist people, people who believe in the spirit, in reincarnation. It’s ceremonial. Not like voodoo, but about how to reproduce a spirit to something existing. Whether you are Christian or Muslim you carry this animist tradition with you.

The mask is the concretising of the spirit. It’s a support for going to the spirit. But it is also about beauty. The structure is beauty. It’s my representation of the beauty of my tradition, the beauty of the spirit tradition. The beauty of the idea of this support for going to the spirit.

You have exhibited widely, also at Dak’Art ‘Off’. How do you see this biennial changing contemporary art in Africa in general and how has it been affecting your career personally?

I’m a simple person. I believe that patience is important. If I do my art without focusing on anything else, then things are going to come by themselves. People are going to call. If I work, it’s because I want to do it, like to do it. But after participating in the biennial people invite me for many projects.

I think the biennial is amazing, I really appreciate the idea, the concept. It’s a great program happening every two years. They have the biennial ‘in’ and the biennial ‘off’. We have more than 100 exhibitions all in all in our city. In one month you can meet so many great artists from around the world.

It’s the biennial of contemporary African art and Africans in the diaspora, and sometimes they invite some other artists. It’s not just painting, they have installations, video, performances, dancing and cinema – it’s interesting because you have so much contact, and you see so much difference in how people think and express themselves artistically.

People come from around the world to participate and experience the biennial. Right now I have an exhibition in Washington D.C. and they know the biennial of Dakar. People are talking about this.

Are you participating next year?

Yes, I have to because I and a conservator friend of mine have a project. There will be another girl also, from Germany I think. All in all there will be two foreign and three Senegalese artists. In February we will all do a workshop and the works done at this workshop will be presented at the biennial. That’s our project.

I was also invited for another show, though. I have to go back to my country in January, and we’ll see what programs I will have, but I will definitely appreciate participating in the biennial.

How do you as a person balance being part of a traditional society and also a global player on the international art scene?

I try to do it in my own way. It is not easy because I’m an artist, but at the same time I am glad to be part of a traditional society. I both love and hate things inside this society. We are now trying to erase certain traditions, like to marry girls very young, or the circumcision. But also, we have some good things, like respect of the parents and the things you do before getting married.

Also in modern there are good and bad things. We are trying to balance these. It’s interesting because I can see the differences more when I’m travelling, that’s why it’s also interesting to travel.

What I see in the Occident is that you are more influenced by the contemporary, modern world than the traditional. The traditions are ‘turned off’. That cannot be better, though. We have to know where we come from to know where we are going. It’s not only good to be ‘going, going’ and forget the past. The past has to be available to everybody.

I try to be on the good way between my tradition, which I will never stop – to take part in it – and at the same time to know that we are in the modern world. We cannot go without it.

What do you wish – or hope – that the viewer takes with her after seeing your work?

I hope they will be curious. That they see something different, ‘cause I try to do something unusual. The artist’s role is like that of the magician – to open people’s eyes. I experience people crying when they come to one of my paintings, because they get such an impression. I hope that people will feel something when they go home.

You mentioned that music plays a big part in your work. Do you feel that it’s possible for the viewer to see your work of art as music – can it have the same emotional effect?

We can say yes. We have so many different kinds of art, but it’s actually the same thing. The music, the cinema, the writing, the singing, the painting – it’s all different kinds, but in the end for people the impression has to be the same.

The feeling you get when you hear the music, you can feel something like that when you see the painting – but in a different way. It’s the same thing you can feel but in a different way, when you read a book. In the end we are all the same, we just have different ways of expressing ourselves.

Do you ever listen to music when working?

Yes, a lot. It’s one thing that can inspire me a lot. Not any kind of music, though, mostly it’s acoustic music. I really appreciate that when I’m working. Kora music.

You have been working at VerdensKulturCentret in Copenhagen for more than two weeks now, painting live in the café area. What reactions have you received from visitors?

A little one was quite shy. Other people came to look more closely. There was a girl working in the kitchen – she saw me working on this nude female figure. At the end I dressed the figure and the girl from the kitchen came the next day and said ‘oh, finally she is dressed.’ She followed the work quite closely, observing the process.

I’m not shy to do a workshop, ‘cause when I work, I am in my element, and it does not disturb me to see people looking around.

It was a fun experience, and not something I’m used to, when working in the studio.

De-fernisering på VerdensKulturCentret

Kiné Aw fortæller om sine kunstværker ved en ‘de-fernisering’ onsdag den 4. december kl. 16-16.45 i VerdensKulturCentret.

Udover Kiné Aws kunstværker er der også mulighed for at opleve den herboende gambianske koraspiller Dawda Jobarteh, der giver koncert efter Kiné Aws artist talk.

Program for dagen:

Kl. 16: Artist Talk ved Kiné Aw

Kl. 16.30: ‘de-fernisering’

Kl. 16.45-17.30: Dawda Jobarteh koncert.

Sted: VerdensKulturCentret, Nørre Allé 7, 2200 København N.

Senegal Denmark Cultural Rally 2013

Kiné Aws besøg i Danmark sker som en del af Senegal Denmark Cultural Rally 2013.

Senegal Denmark Cultural Rally 2013 er det første dansk-afrikanske Cultural Rally. Projektets vision er at skabe et fundament for dialog og samarbejde mellem Danmark og de nye vækstlande i Afrika.

Senegal Denmark Cultural Rally har fokus på vestafrikansk populær musik, afrikansk samtidskunst og senegalesisk film.

Senegal Denmark Cultural Rally er en del af initiativet Africa Denmark Rally, der i efteråret 2012 blev iværksat af projektleder Aziz Fall i tæt dialog med Det Danske Kulturinstitut og de afrikanske samfund i Danmark.

Visionen er at skabe stærke, gensidige bånd mellem relevante aktører baseret på ligeværdighed og ‘co-creation’ med fokus på bæredygtighed og innovation. Projektets undertitel er således ‘Denmark works with Africa’.