Beirut (HRW): More than half of the nearly 500,000 school-age Syrian children registered in Lebanon are not enrolled in formal education, Human Rights Watch says in a new report.

Although Lebanon, which is hosting 1.1 million registered Syrian refugees, has allowed Syrian children to enroll for free in public schools, limited resources and Lebanese policies on residency and work for Syrians are keeping children out of the classroom.

Growing Up Without an Education’: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon,” documents the important steps Lebanon has taken to allow Syrian children to access public schools.

Many Syrians not registered with UNHCR

Access to education is crucial to help refugee children cope with the trauma of war and displacement, and gain the skills to play a positive role in host countries like Lebanon and in the eventual reconstruction and future of Syria, Human Rights Watch said.

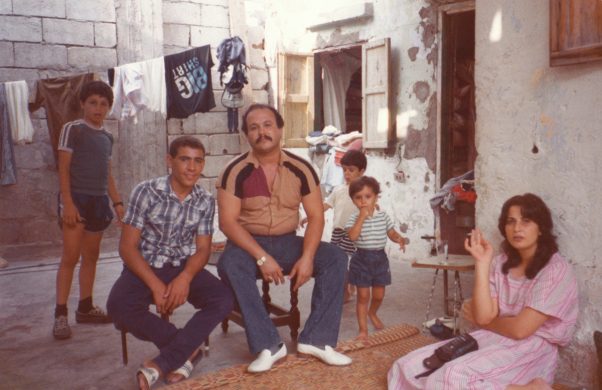

In November and December 2015, and February 2016, Human Rights Watch conducted 156 interviews with Syrian refugees, gathering information about the situation of more than 500 school-aged children. Some had been out of school since arriving in Lebanon five years ago. Others had never stepped inside a classroom.

An unknown number of out-of-school children are among the estimated 400,000 Syrians in Lebanon not registered with UNHCR, which ceased registration of Syrian refugees in May 2015 at the instruction of the Lebanese government.

Selling chewing gum on the street

In September, the Education Ministry announced plans to enroll 200,000 Syrian refugees in formal public education, with international support, as part of the Reaching All Children with Education policy adopted in June 2014.

The number of classroom spaces for Syrian children in Lebanese public schools has increased every year since the Syria conflict began in 2011. In 2015-16, however, schools still turned away Syrian children because available spaces were not necessarily located in areas of need, or children faced other barriers. Of the 200,000 school spaces that donors committed to funding for Syrian children, almost 50,000 ultimately went unused.

Rana, 31, who fled from the outskirts of Damascus to Lebanon in 2012, said she had to quit her job in a pastry shop because she feared arrest after her residency expired. As a result, she could not afford to send her children to school. Now, her 10-year-old son Hamza is selling chewing gum on the street.

Syrian children face barriers in schools

Kawthar, 33, said that when she tried to enroll her children in fall 2015, one school demanded several documents that the Education Ministry does not officially require, including vaccination records she left behind when fleeing Syria.

She was eventually able to enroll her children, but pulled them out after three months because they never received textbooks and she could not afford to keep paying for their transportation.

Syrian children with disabilities face particularly daunting challenges. Public schools, which have a poor record including Lebanese children with disabilities, often reject them, saying they lack the resources or skills to educate them. When Syrian children with disabilities are able to enroll, public schools do not ensure they receive a quality education on an equal basis with others.

Some Syrian children have benefited from non-formal education programs run by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), often in informal refugee camps. But some groups told Human Rights Watch that the Education Ministry withdrew support for their programs last year, or that they discontinued programs because it was unclear what they were allowed to provide. The Education Ministry has since adopted a policy framework for non-formal education, and in January launched an accelerated learning program for children who have missed two or more years of school.

However, officially approved programs to reach children who cannot attend formal schools remain limited.

Lebanon says that lost revenue due to the war in Syria and the burden of hosting refugees have cost the country an estimated US$13.1 billion.

Lebanon should ensure that its generous enrollment policy is properly implemented and that there is accountability for violence in schools, including corporal punishment, Human Rights Watch said.

The Education Ministry should allow NGOs to provide regulated, quality non-formal education, at least until formal education is accessible to all children in the country.

The government should revise its residency requirements and allow those whose status has expired to regularize. It should also operationalize its Statement of Intent presented at a London donor conference in February and review the regulatory frameworks related to work authorization for Syrians.